Replication failures from fishy science

A fishy start to my career

Although I now work on Homo sapiens, I got my start in the world of science studying the humble blind cavefish, Astyanax mexicanus. These are fascinating creatures that have evolved to live in absolute darkness and feast on bat guano. It’s a rare corner of science where you can use the word troglodytic without any negative connotations.

My undergraduate and Master’s advisor, Sheryl Coombs, was particularly interested in how fish orient to currents, a behavior called rheotaxis. For most species at most stages in their lives, if you plunk them in moving water, they face upstream. We wanted understand the multi-sensory basis of this behavior, because although it is a simple one-dimensional output it can rely on input from almost any sensory system: vision, vestibular cues, their flow-sensing lateral line system, smell, touch… you name it.

Swimming upstream

The literature on the subject stretched back about 100 years, with a paper every 5-40 years trying something new and declaring that fish do or do not use a given sensory system. Lyon in 1904 put fish in a dark tank with running water, cracked the lid, and concluded they needed vision to orient to currents. Hofer in 1908 declared they didn’t need vision, but that they needed the lateral line system instead. Dijkgraaf repeated Lyon’s experiments in 1963 and declared him correct. It flipped and flopped a few more times after that. The literature was a mess.

Of course, the elephant in the room was that our friends, the blind cavefish, can orient to currents just fine absent eyes. Vision is clearly not strictly required. Enter John Montgomery in what the Zoomers refer to as the late 20th century (1997). He ran very careful experiments with new techniques to answer the question once and for all (Montgomery et al. 1997). He knocked out the lateral line systems of three species of fish—including blind cave fish—and found that at low flow speeds, the lateral line was necessary, but not at high flow speeds. The replications and failed replications throughout the 20th century were explained by what psychologists these days are calling a hidden moderator: flow speed.

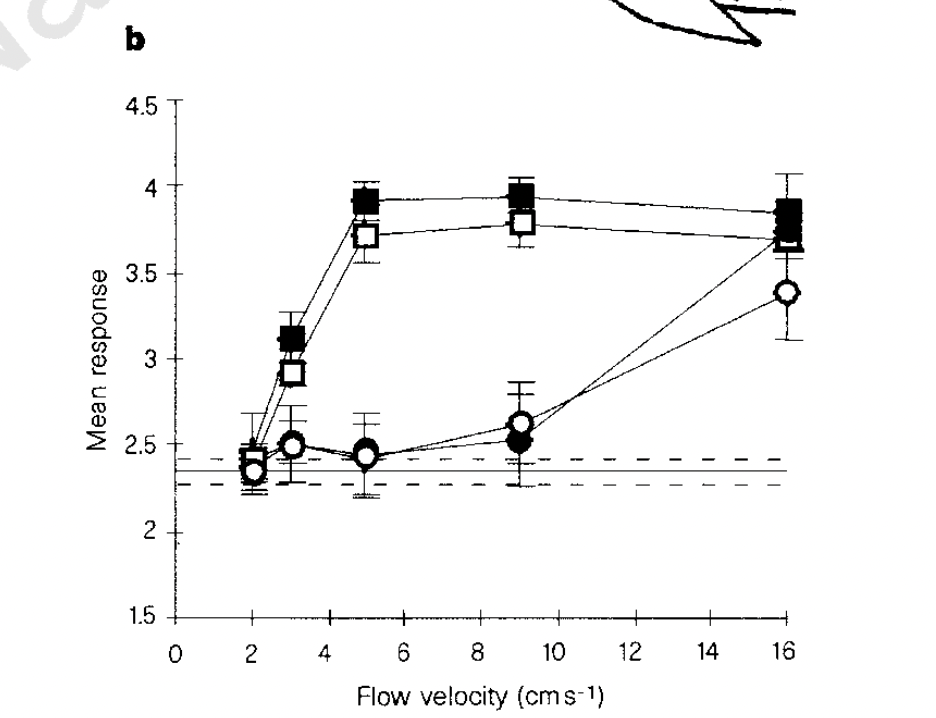

The results couldn’t be more obvious and I’ve included them below. The circles are with the lateral line fully knocked out and the squares are with the lateral line intact. The open and closed circles are interesting here as well. Without getting too into the weeds, the circles indicate scraping off the lateral line system’s cells or treating the fish with cobalt chloride. The squares indicate using a specific antibiotic to selectively knock out part of the lateral line system and the control. Solving a long-standing debate, this work was rightly published in Nature. A rarity for the field.

A failed replication.

One of the really cool things about blind cave fish is that they’re the same species as a sighted fish called a Mexican Tetra, which looks entirely different (it has eyes). If you breed two blind cave fish from different caves, they generally produce sighted offspring. For one of the first experiments I designed, more than a decade ago, I wanted to redo the Montgomery et al. work, comparing sighted and blind fish. We thought that maybe the blind fish would be a bit more sensitive, as they had more elaborate lateral lines and no eyes to take up valuable neural real estate. Going downstream is also terrible for them. Leaving the cave during a flood means certain death.

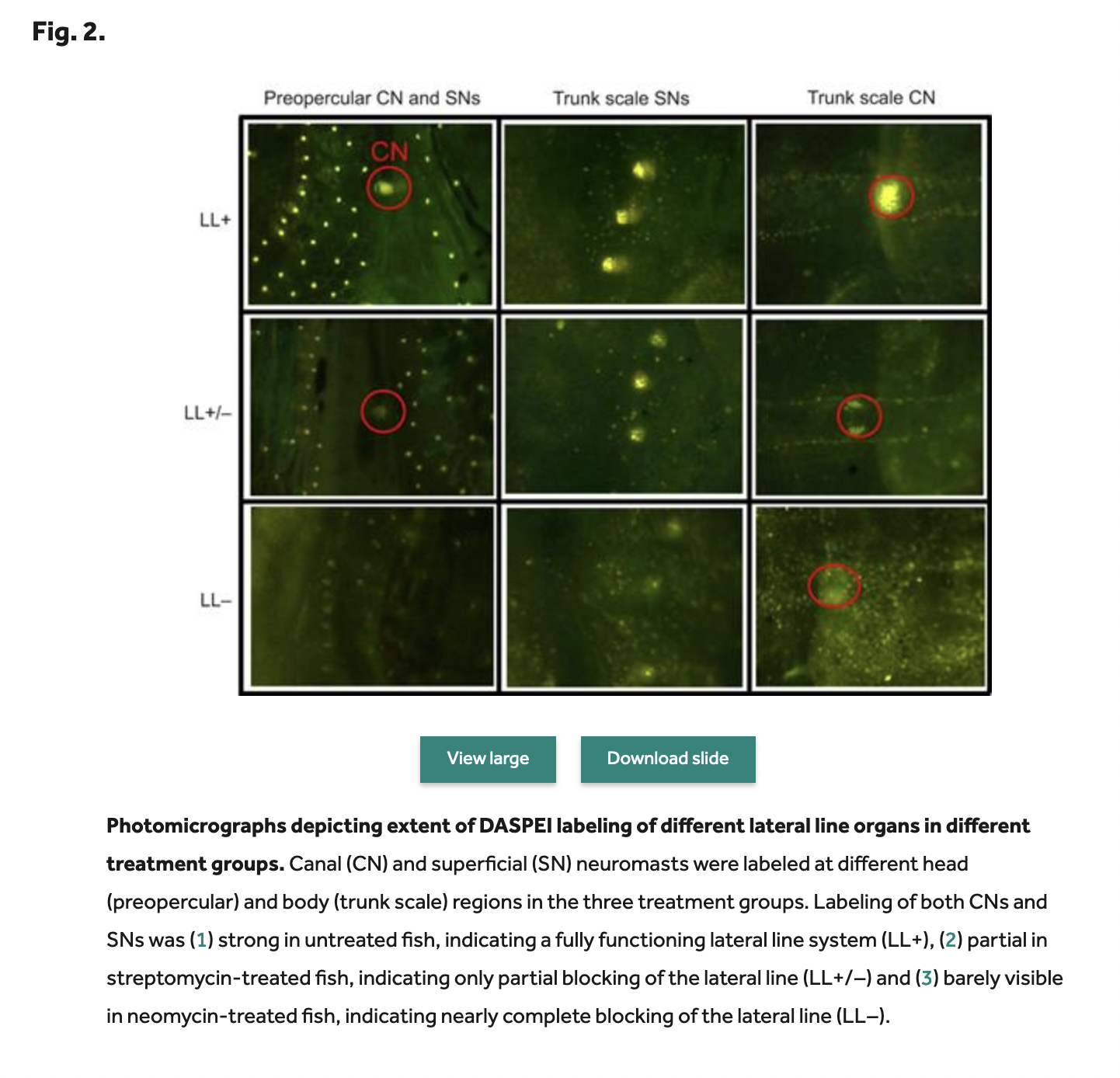

I needed to knock out the lateral line. The prevailing wisdom at the time was that Cobalt Chloride could be unethical to use, as it is more globally toxic. Gentamycin supposedly only knocked out part of the lateral line, but its cousins neomycin and streptomycin took out the whole thing. It’s reversible too, so two weeks later the fish are fine and back to normal. You can also verify the lateral line is knocked out with a harmless fluorescent dye called DASPEI.

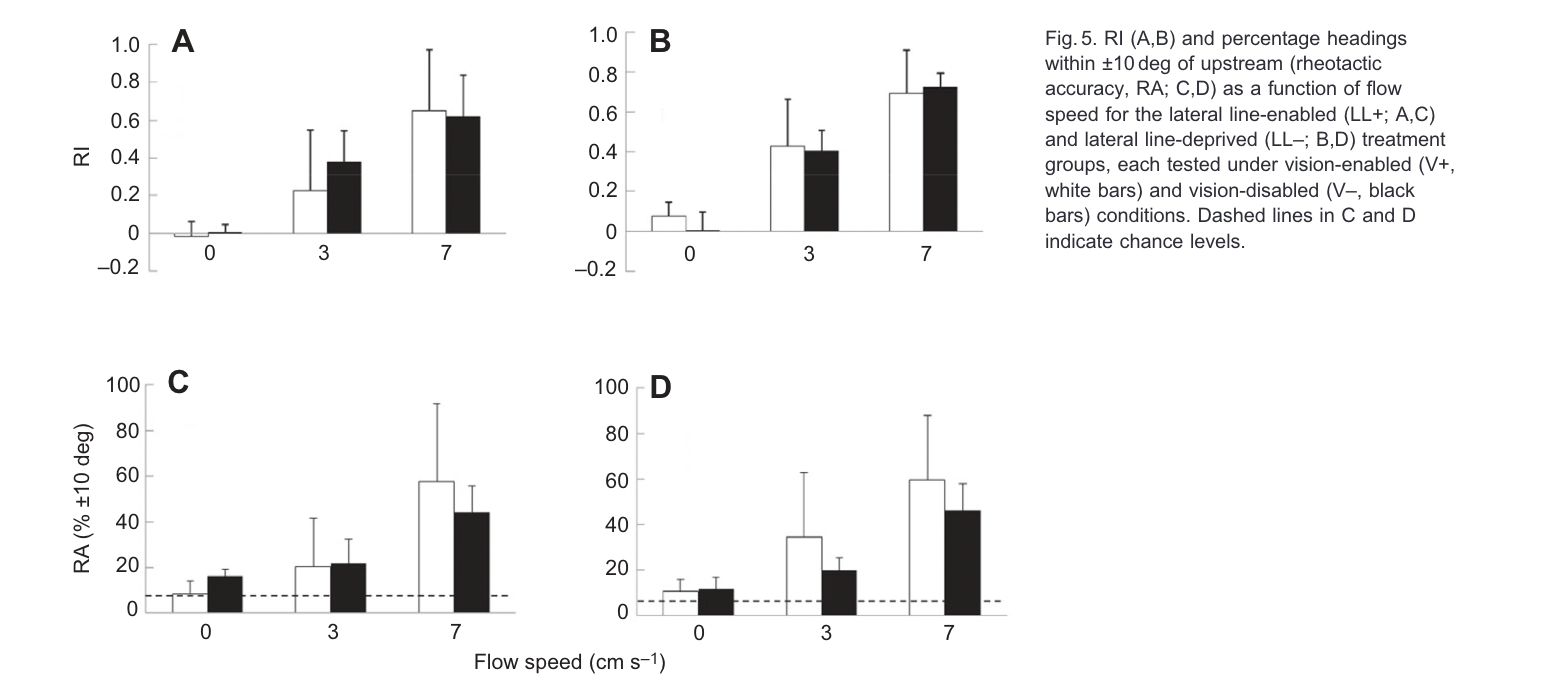

I learned all of these techniques, knock their lateral lines out, and the damndest thing happens (Bak-Coleman et al. 2013). The fish are pointed upstream just fine at speeds of 3 and 7 cm/s. These are well below what was required in the Montgomery work. Same species, and this is absent both a lateral line and visual cues. It didn’t really matter how you measured it or what stats you ran. This is a godsend because I knew so little about stats at the time and even used dynamite plots.

Something fishy is going on

Montgomery in 1997 had cleverly replicated the effect across three very different species. One was a saltwater fish that lived in Antarctica, the second a species endemic to New Zealand that lived in fast-moving freshwater streams. The third, our blind cave fish, found in mostly still, pitch-black water. We have the gamut of temperature gradients, flow gradients, across saltwater and freshwater. The effects are consistently huge, as were ours across the sighted and blind morphs.

We couldn’t write this one off to heterogeneity or random noise. QRPs, which were not formally defined at the time, might jitter a p-value below .05, but they aren’t going to generate consistent psychometric functions across multiple species of fish and conditions. Fraud was likewise not a satisfactory explanation, as we knew the authors of the original study well, and they were fastidious with data preservation and more than happy to mail us their video cassettes (we declined, shipping from Australia was beyond our budget). It was clear nothing metaphorically fishy was going on, but equally clear something literally fishy was going on. We found ourselves back in the trap of Lyon, Hofer, and Dijkgraaf, trying to reconcile obvious but conflicting results.

Teasing it out

Sheryl, being the epitome of a good scientist, put the whole lab to work reading the literature to figure out what was going on. We went through every study on the orientation of fish to currents, examining all the details of the methods. How fast was the water? How did they create the flow? Turbulent? What species? What are the characteristics of that species? What did they use to knock out the lateral line? How old were the fish?

Something jumped out at us. If you physically damage the neuromasts via scraping or something very cold, you tend to knock out rheotaxis. The same was true of using cobalt chloride, which was found post-Montgomery to be toxic in fish at the doses used. Other studies with similar results had replicated these methods. We hadn’t used them out of a duty of care to the fish. Maybe the fish weren’t just unable to orient to currents, they were poisoned or physically harmed.

It’s a nice story that neatly explains the discrepancies, except there’s a confound. The lateral line system is divided into two separate systems, one that is on the surface of the fish and the other that is deeply buried in canals. They function differently, with the superficial system detecting low-frequency flow and the canal system detecting high-frequency flow. An alternative explanation is that the superficial neuromasts are important, the canals aren’t. Gentamycin was believed to be selective for canals, so we can’t tease apart this possibility from argument alone. We also weren’t really in the mood to start laboriously scraping and poisoning fish if we didn’t have to.

We started digging into the various aminoglycoside antibiotics and found that some are much better than others at reliably knocking out the lateral line at standard doses (Kulpa et al. 2015). For a host of reasons, this can possibly explain the apparent selective blocking of the lateral line system by Gentamycin. It can explain why gentamycin didn’t stop rheotaxis in Montgomery, but doesn’t get us any closer to figuring out why we couldn’t stop rheotaxis using the good stuff. It did, however, point us in the right direction for making sure we knocked out the lateral line—superficial and canal.

With this in hand, we started looking at the other differences. Another thing stuck out. Setting aside the Montgomery results on blind cave fish, rheotaxis seemed to depend on the lateral line for fish that spend their time on the substrate (Bak-Coleman Et al. 2014). Sure enough, when we went to test in a couple of species the results were clear. The two non-cavefish species Montgomery tested, despite their differences, were bottom-dwelling fish. The pattern was fairly consistent across the literature. We also pulled at other threads, the role of turbulence and and developmental stage. The list goes on, but we conducted a ton of experiments in a pretty short 2-3 year time span. We left one, in my memory, in the file-drawer which will be a story for the next blog post.

The story we put together was a complicated one but mechanistically made sense. Fish that are coupled to the substrate need the lateral line, because that coupling deprives them of vestibular cues. If fish have vision, they use it. How you knock out the lateral line matters, both in terms of toxicity and selectivity but also because some of the drugs just aren’t very reliable. Recently, I teamed back up with my Master’s advisor and John Montgomery of Nature 1997 fame to write a review article summarizing this and other work (Coombs, Montgomery and Bak-Coleman 2020). Give it a read if you want to hear more of the story.

Fish buckets, uphill both ways.

It’s been a while since I’ve done work on fish, and I’ve been almost exclusively working on humans for at least the last 6-7 years. Anyone conducting research into human behavior invariably runs into discourse around failed replications, what they mean, how they should be interpreted, and how to prevent them. These discussions often extend to the whole of science, suggesting how all fields should conduct their work, engage in replication, interpret replications, and so forth.

Whenever these discussions come up, I find myself at times at odds with some of the prevailing thinking. Tonight, it occurred to me that some portion of this disconnect goes back to my early work in the area. My first attempt at science was failing to replicate a study in Nature, but it felt exactly nothing like failing to replicate a study in Nature on humans might feel. It didn’t erode my faith in the original results or raise any concerns about the researchers. It was a mystery to solve, and the authors of the original paper felt much the same way.

There were parsimonious explanations that could have been cited to explain the replication failure, more than enough theoretical grounds to reject the old finding. But rejecting that finding was not the goal. Rather, the goal was to develop a cohesive understanding of all of the data in their totality. There were no concerns about fiddling with p-values because the effects were visible in the rawest of data—video tapes of the fish swimming. Nor were there worries about outcomes—it’s hard to mess up measuring a fish swimming upstream vs. not. We didn’t have pre-registration in any formal sense, but both labs had protocols before running every set of experiments, detailing what we were doing and why. QRPs hadn’t been defined but they wouldn’t have done us any good, because we weren’t hanging our hats or theory on the p-values from a single statistical test. Our file drawers were tiny, and limited to a single study we realized was hopelessly confounded.

I’m reading what I wrote in the last paragraph and recognizing that it sounds a lot like an old man waxing poetic about the simpler times before scientific reform, the replication crisis, and this QRP-hacking-fraud hooey. When we’d carry fish uphill both ways (four floors up, four down) just to look at the pure, unadulterated data without those fiddly statistical tests. When replication was just part of an honest day’s work, etc., etc…

This is most assuredly not the point of this post. I don’t think that research was better, and there’s plenty I’d do differently—particularly in the analysis. Nor do I think it was made possible because the standards were more lax then. Animal behavior hasn’t come that far, and I’m pretty sure we could conduct and publish the exact same experiments today. Probably with the same stats. It also isn’t the case that animal behavior is free from problems, as anyone following the spider literature in early 2020 is well-aware.

While I’m proud of that work, I’d stop short of saying I’m 100% certain we got it right. But I’m sure we made progress. There could be a masters student in a lab trying and failing to replicate our research. Unlike what one might expect, the thought is absolutely thrilling, and would probably be the coolest email I could receive short of a tenure-track offer. I would love to find out that I’d gotten something wrong, that the story is even richer or simpler than I’d supposed. Especially if I’m not the one carrying the bucket.

Deforming Science

In reflecting on the few corners of science I’ve experienced, I can’t help but wonder what else is out there. The fish story is one of failures to replicate, superficially resembling our discourse in social science. Yet, the similarities between fish and the replication crisis as we understand it today start, and end, at the word replication. In fish orienting to currents, the “replication failures” dated back to not only before the replication crisis—but only four short years after Pearson’s p-values and decades before Fisherian p-values and Neyman-Pearson Null Hypothesis Significance Testing. There was no p-value to p-hack when this century-long train of failed replications started.

Obviously, the same is not true across science, and some findings are entirely propped up on escaping from the file-drawer, finding the right path in a forking garden, or outright fraud. Some fields really need accountability more than anything to make sure they don’t engage in these temptations. Still, others might not have any issues with replication but spend considerably more time just cataloging things as fodder for other research. Or they might have clear theory that leads to obvious effects which would replicate if true, but face challenges of how to physically create a mechanism for collecting the requisite data. Some disciplines might not have a snowflake’s chance in hell of ever replicating anything, because the opportunity, ethical or practical costs of replication may not be worth it. I’m sure I’m missing a host of other possibilities.

The point is that when we talk about replication crises, scientific reform, open science, or how science “should be,” I suspect the biggest point of contention is that very few of us have identical ideas of what science even is. We all carry some history of the research we’ve done, the methods we use, the questions we ask, and the people we’ve looked up to. For me, that history has led to skepticism that science is well enough defined to be capable of reform. I struggle to understand how we could give ESP replication failures and rheotactic replication failures the same diagnosis and prescription. Maybe the answer instead is to deform science, recognizing it for the amorphous blob that it is and trying to figure out how we can use it to sort out what the hell is going on.

Coda

This is getting some traction, so I thought I should provide and update on what’s happened in the field since. A paper in 2017 was published in Nature once again claiming that the lateral line is essential based on some elegant experiments in larval zebrafish (Oteiza 2017). I believe these experiments, and they provide some deep insight into the mechanism, at least for these younger fish. However, we also know that the mechanism seems to change throughout early development (Bak-Coleman, Smith and Coombs 2014)

We know this also isn’t broadly true, we can take the lateral line out and still get rheotaxis in adult fish. Oddly, despite having sent my work to some of the authors of that study… none of this complexity is noted in the write-up. Perhaps someone will come along in a few years, fail to replicate that in adults, go back into the literature, and start hauling buckets.

References

-

Lyon, E. P. (1904). On rheotropism. I.—Rheotropism in fishes. American Journal of Physiology--Legacy Content. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1974.tb01173.x/full

-

Dijkgraaf, S. (1963). The functioning and significance of the lateral-line organs. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society, 38, 51–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.1963.tb00654.x

-

Montgomery, J. C., Baker, C. F., & Carton, A. G. (1997). Montgomery et al. 1997 rheotaxis. 389(October), 960–963.

-

Bak-Coleman, J., Court, A., Paley, D. A., & Coombs, S. (2013). The spatiotemporal dynamics of rheotactic behavior depends on flow speed and available sensory information. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 216(Pt 21), 4011–4024. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.090480

-

Kulpa, M., Bak-Coleman, J., & Coombs, S. (2015). The lateral line is necessary for blind cavefish rheotaxis in non-uniform flow. Journal of Experimental Biology, 218(10), 1603–1612. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.119537

-

Bak-Coleman, J., & Coombs, S. (2014). Sedentary behavior as a factor in determining lateral line contributions to rheotaxis. Journal of Experimental Biology, 217(13), 2338–2347. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.102574

-

Coombs, S., Bak-Coleman, J., & Montgomery, J. (2020). Rheotaxis revisited: a multi-behavioral and multisensory perspective on how fish orient to flow. In The Journal of experimental biology (Vol. 223, Issue 23). NLM (Medline). https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.223008

-

Oteiza, P., Odstrcil, I., Lauder, G., Portugues, R., & Engert, F. (2017). A novel mechanism for mechanosensory-based rheotaxis in larval zebrafish. Nature, 547(7664), 445–448. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature23014

-

Bak-Coleman, J., Smith, D., & Coombs, S. (2015). Going with, then against the flow: Evidence against the optomotor hypothesis of fish rheotaxis. Animal Behaviour, 107, 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.06.007

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: