Retire the P-Curve (On Twitter)

The P-Curve’s bold claims

In science, there is a common concern that large swaths of the published literature are simply “wrong”. Although these concerns have been around a long time, they have become a centerpiece of scientific discourse over the past 15 years. Rationales for these concerns are wide ranging, but generally center on the overabundance of statistically significant findings in the literature. Typically, this is chalked up to some combination of the file-drawer problem (most research going unpublished) or Questionable Research Practices—encompassing a wide range of behaviors that might convert a non-significant finding into a significant one. Scientists find themselves staring at the literature, trying to discern where the baby ends and the bathwater begins. What do we throw out? What do we keep? How can we trust that new results are not P-Hacked?

Enter the P-curve.

Developed in 20131, P-Curves have been the stickiest among a family of meta-analytic tools designed to confront selection bias going back 40 years 2. Their logic is fairly straightforward, for a given (and fixed) power, the distribution of p-values takes on a characteristic shape. If power is sufficiently high, this distribution will be skewed such that smaller p-values are more common than those close to .05. Without loss of generality, we can calculate a p-curve for the simplest possible case—a one sample Z-Test.

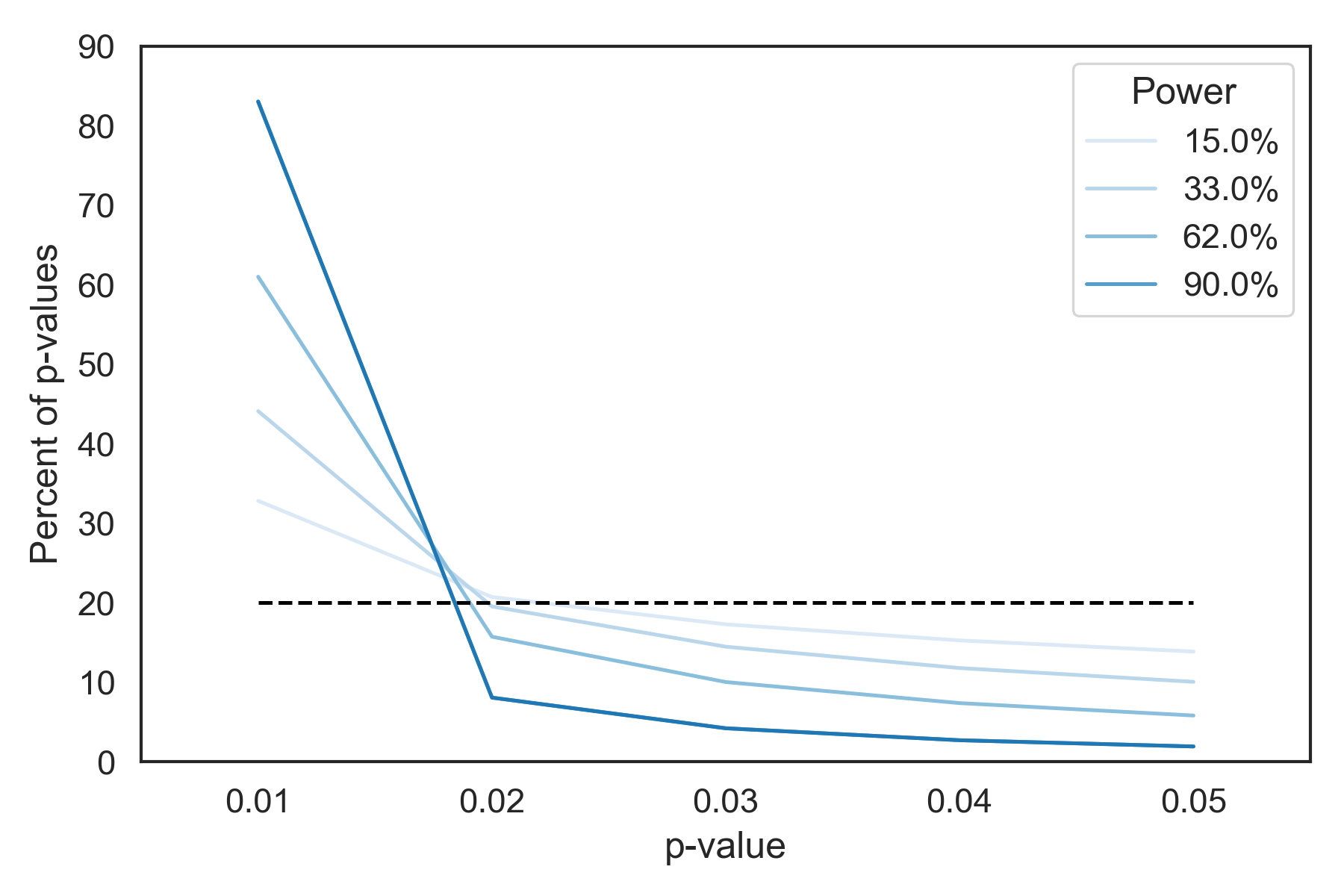

P-Curves calculated assuming a 1-sample Z-test at various levels of power.

P-Curves calculated assuming a 1-sample Z-test at various levels of power.

Note that as power increases to 90%, the probability of getting a p-value between .01 and .05 drops to less than 20%. For 62% power, the chance of getting a p-value between .025 and .05 is only 8%. Armed with this model, what might we conclude if a study on two effects reports p values of .027 and .039 with 62% average power? The probability of this occurring under the p-curve model is less than 1%.

P-Curve: Polygraph and Baton and of the stats cop

This feature of p-curves has become the polygraph and baton of self-styled stats cops on Twitter. They argue that an abundance of p-values nearer to .05 cannot be explained by chance and therefore constitutes evidence of p-hacking. Every few months, some study gets a bit of news attention. This corner of Twitter circles the p-values, notes how many are near .05, and then a pile on begins.

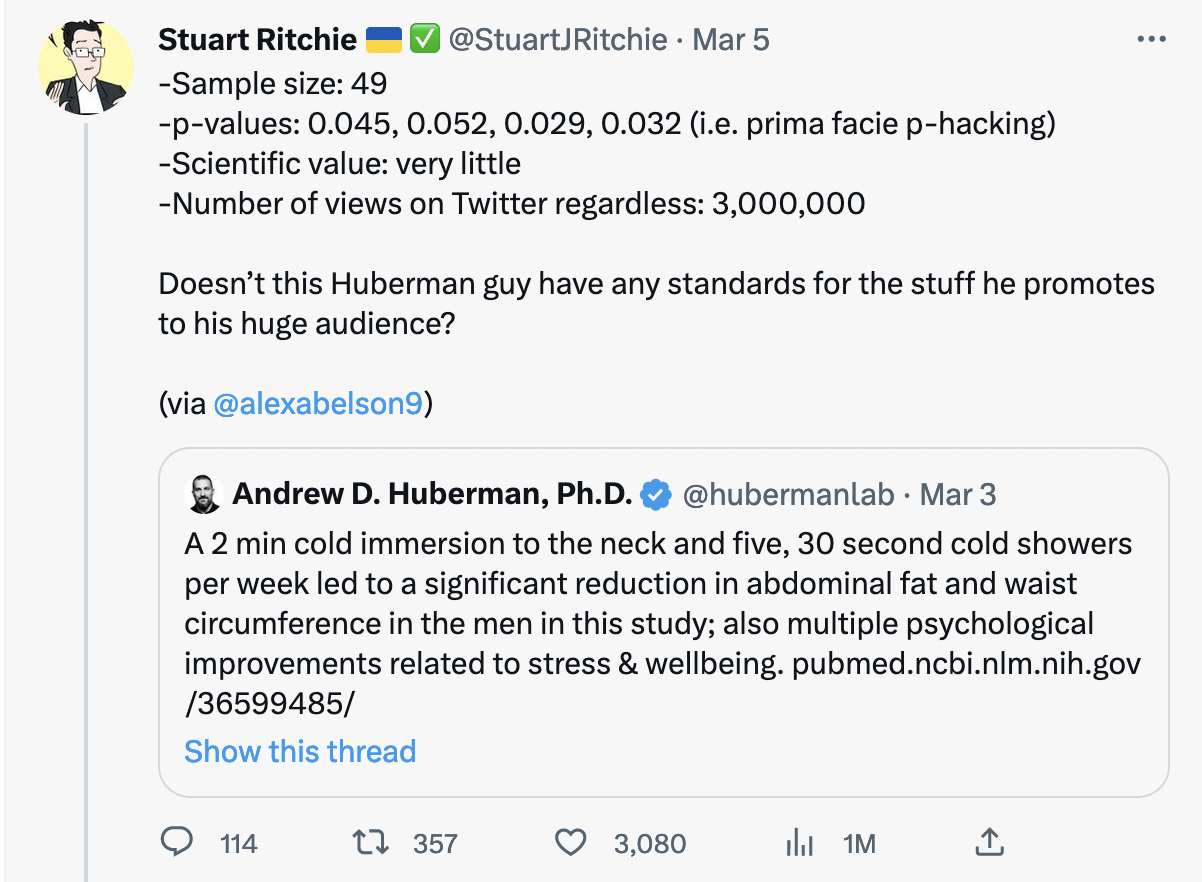

Informal application of the p-curve to assert p-hacking in a study on cold exposure

Informal application of the p-curve to assert p-hacking in a study on cold exposure

Of course, there is little doubt that published studies will often require debunking or benefit from critique, and the cold exposure study had its share of issues. However, far too often, this dynamic emerges as a consequence of an early career researcher’s work that found its way into a viral news story. If the researcher followed open-science principles, their data and code are downloaded by dozens of sleuths that effectively reverse p-hack the data into non-significance then hold it up alongside the p-curve as evidence of p-hacking. As you might expect, this does not make open science a particularly welcoming place.

What makes these p-curve critiques distinct from something like discussing potential confounds or the appropriateness of statistical tests, is that they carry with them judgement of either the researcher’s abilities or moral standing. They necessarily insinuate that a researcher either does not understand that you can’t engage in QRPs, or has done so knowingly in an attempt to mislead the scientific community for personal gain. These are hefty allegations, and they’re gonna need solid evidence. Does the P-curve give us that?

P-Curve: P-Hacking to detect P-Hacking

As initially conceived and often implemented, these p-curve type methods are to be used on chunks of the scientific literature specified a priori. This has its own issues and caveats, which are discussed this excellent post. However, advocates of the p-curve have taken this a step farther, suggesting it should be used to evaluate individual studies. Even for studies reporting only a pair of results, journal editors are encouraged to seek explanation from authors with “unlikely” patterns of p-values… or force them to run additional experiments. Lakens writes:

What should you do as an editor when you encounter a set of studies with p-values that are relatively unlikely to occur? First, you can ask the authors to discuss the situation. For example, when you explicitly mention the set of studies becomes more probable when a non-significant finding is added, the authors might be happy to oblige. Second, one of my favorite solutions is to decide upon an in principle acceptance (assuming the article is fit for publication), but ask the authors to add one replication. The authors are guaranteed of publication irrespective of the outcome of the replication, but we have a better knowledge of what is likely to be true.

Perhaps this sounds good in principle, but consider it in practice: A twitter data-sleuth sees a news story making the rounds, and decides to examine the paper. They notice the reported significant p-values between .025 and .05, calculate the probability that would have occurred by chance, and find that it is low. Excitedly, they post to Twitter that the surprising, news-worth headline is probably p-hacked. Clout rains down.

Of course, they wouldn’t have calculated this quantity had the p-values been smaller. The decision to run the analysis depended on the data, such that they engaged in p-hacking to detect p-hacking. This could be made worse, as there are plenty of researcher degrees of freedom in estimating probability from a p-curve. At the end of the day, it’s no different than seeing a trend in a scatter plot and finding a regression line yields significance.

Alternatively, the researcher might argue that they apply the test to every paper they encounter. I seriously doubt this is the case for anyone (who has the time?), but this is just data-dredging the published literature for evidence of p-hacking. Unless they tweet every time someone’s paper has plausible p-values, they’re cherry picking the instances in which the test indicates p-hacking. It’s no different than a scientist who claims they can avoid p-hacking by testing every possible relationship and reporting those that are significant.

Worse, they often double down–pulling the data and considering alternative analyses that would have produced non-significance. All of this occurring is conditioned on the data itself, such that the a fair chunk of this sleuthing winds up engaging in the very thing it seeks to eradicate. In practice, applications of the p-curve—particularly on Twitter—are simply p-hacking to prove p-hacking. The shoemaker’s children go shoeless.

A model like any other

At it’s core, the p-curve is a model, and inferences drawn from it are only as good as the model assumptions. One of its core assumptions is that the p-values are independent. This is rarely the case within a single paper, as often the reported effects are on the same phenomenon measured in a a similar way from a similar population. This increases the probability that effect and sample sizes are in the same neighborhood, as well as the p-values they generate.

It likewise assumes that all experiments would have been conducted, regardless of the outcomes of of previous experiments. This too is rarely the case, as findings guide additional research. As Richard Morey pointed out, this is a non-trivial distinction with profound consequences for how we interpret findings after the fact.

P-Curves further require that effects are not heterogenous, and that null effects are precisely zero such that they don’t bleed into the p-curve at a rate higher than expected by chance. With discrete outcomes, p-values can only take on finite values, deviating from the smooth p-curve. Violating any of these assumptions, and especially many of them, renders inferences drawn from a p-curve analysis unreliable.

What P-Curves miss

Even if a p-curve’s assumptions are met, and the data have plenty of tiny p-values, that provides no evidence the inferences drawn are correct or free from p-hacking. Consider a situation in which a researcher knowingly includes a confound that produces a strong effect. This is a QRP if ever there were one, yet a P-Curve analysis would have us convinced the paper contains evidence with no indication of p-hacking. In a sense it does, but only that the confound is indeed a confound.

This could also happen inadvertently, if a researcher simply selects an inappropriate model for their data. Perhaps the strong effect is simply violating assumptions of equality of variance, or normality. Maybe their model is a bit overfit, or there’s post-treatment bias. Perhaps the model is perfectly fine, but the inferences drawn from it are incorrect given the nature of the data.

It’s unfair to assume p-curves, or any tool, should be able to tell us all of these things. Sorting out if a paper provides useful evidence requires a deep understanding of the inference methods, the data collection process, and the domain knowledge that converts the numbers and maths into something we can understand and care about. But this is precisely the point—we shouldn’t expect to be able to pass any and all papers through a statistical tool and determine much of anything about its value.

By imbuing the p-curve with special and unquestioned power to discern fact from fiction, we’ve created a tool that can be weaponized to push junk science. Consider a recent meta analysis4 which leveraged the p-curve as evidence of pre-cognition. Just as Twitter sleuths can p-hack the p-curve to dunk on a paper for internet points, people trying to push scientific disinformation can do the same to demonstrate the validity of their claims.

The take-home

Scientists, pressed for time, too often treat statistical models as oracles that feast on data and yield answers to life’s deepest questions. The reality is that models are quite simple things, which have little to no clue what we want to know and yield an answer regardless. They’re a bit like a less chatty chatGPT. Only if we understand their strengths and limitations can we apply them in a way that will yield useful inference.

Statisticians have yelled themselves hoarse over the paste decade, encouraging scientists to understand what their models can and can’t do, and what their output can and can’t tell us. Scientists, however, have gone a different route—on a crusade against QRPs with much less concern over whether a QRP-free paper yields valid inference. In this quest, the P-Curve has become yet another oracle that we assume can force a distribution of p-values to confess if they were p-hacked.

When a paper differs from the expected distribution, it only tells us that—not why. It could be that the assumptions don’t hold, bad luck on the authors part, null findings stuck in peer review, p-hacking, or just that the rest of the results are somewhere else in the paper. Even when the data match expectations, there’s no guarantee the inferences in the paper are correct. Expecting the p-curve to be the one statistical test that we can uncritically apply to any dataset is madness. There’s no easy substitute for engaging deeply with a papers methods, data, and conclusions.

The P-curve, for whatever value it may hold, is used on social media in the precisely way we’re all taught not to use statistics. Stats cops read paper after paper, and when the p-values in one look suspicious—they form a hypothesis that it was due to p-hacking. When they run a p-curve, sure enough, the data supports their hypothesis. It’s data dredging, cherry-picking, and HARKing all in one. Worse, their hypothesis leads to the conclusion that they can publicly humiliate the author for their transgression. This isn’t constructive criticism, nor is it effective evaluation of the merits of a paper. It’s just cyberbullying.

References

-

Simonsohn, U., Nelson, L. D., & Simmons, J. P. (2014). P-curve: a key to the file-drawer. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 143(2), 534–547. https://doi.org/10.1037/A0033242

-

Hedges, L. v. (1984). Estimation of Effect Size under Nonrandom Sampling: The Effects of Censoring Studies Yielding Statistically Insignificant Mean Differences. Journal of Educational Statistics, 9(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.2307/1164832

-

Bem, D., Tressoldi, P., Rabeyron, T., & Duggan, M. (2015). Feeling the future: A meta-analysis of 90 experiments on the anomalous anticipation of random future events. F1000Research, 4. https://doi.org/10.12688/F1000RESEARCH.7177.2

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: