Rigor Desiderada

Yada, Yada, Falsificada

On June 16th, Stephanie Lee released an article in the The Chronicle detailing a new chapter in a long-running scandal over data mishandling in a now-retracted paper about honesty. We’ve come to learn that a second researcher is being investigated by Harvard, and has currently been placed on leave. While the full report has not been released (and may never be), it looks a lot like Harvard found something pretty damning. If none of this sounds familiar, I suggest reading her article before going much further.

Shortly after Stephanie’s article, Data Colada announced a four-part blog series entitled “Data Falsficada” examining fraud on the part of Harvard Business School Professor Francesca Gino. This blog series is ostensibly a teaser of a longer report, compiled starting in 2021 by the Blog’s authors and other “anonymous researchers.”

The first of a four-post series on Data Falsificadahttps://t.co/hmKOxlsqBX

— Data Colada (@DataColada) June 17, 2023

Blog post 1: Oh sheet.

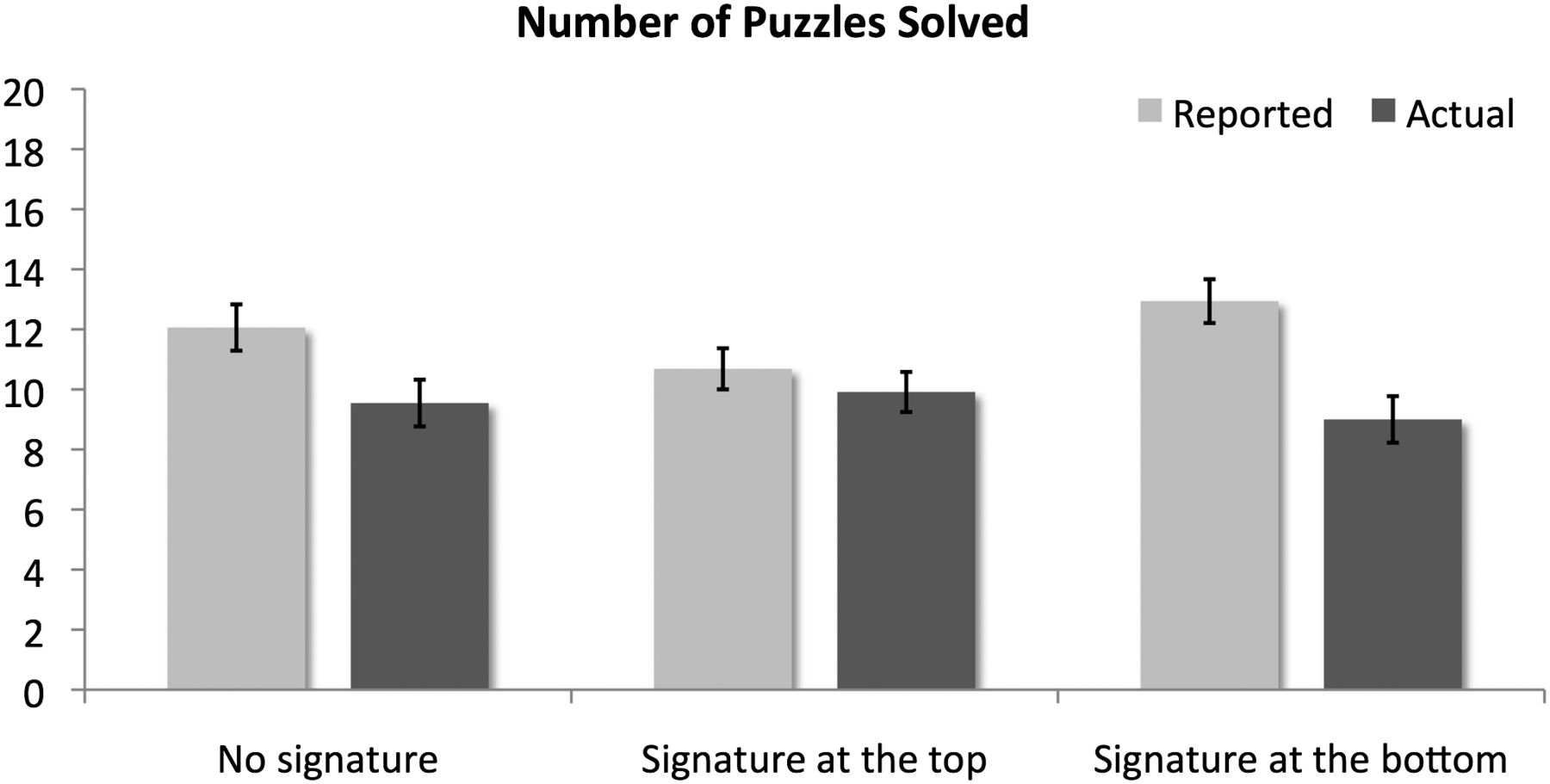

The first blog post examines already-retracted study, which claimed to show that signing at the top of a document leads to greater dishonesty than signing at the bottom. The key finding can be found in this very chic drop-shadow dynamite plot:

Figure 1 from original manuscript. Caption: “Reported and actual number of math puzzles solved by condition, experiment 1 (n = 101). Error bars represent SEM.”

Figure 1 from original manuscript. Caption: “Reported and actual number of math puzzles solved by condition, experiment 1 (n = 101). Error bars represent SEM.”

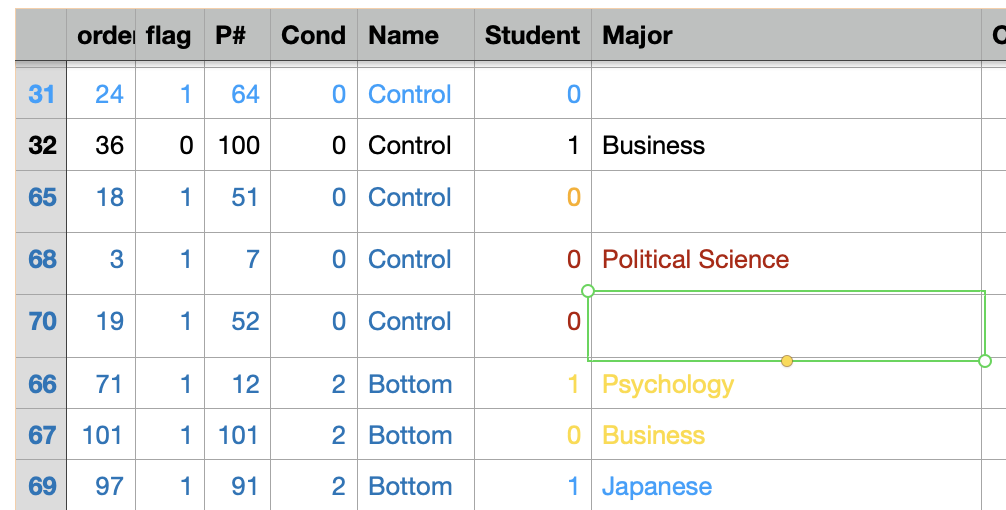

Data Colada’s blog post provides compelling evidence that rows were moved around inside of an excel file. The trick here is that excel files are kinda neat, and don’t both re-organizing the deeper data every time you move something around. Instead, they store a record of what went where. Digging into this record shows that a few of the observations appear to be out of order or duplicated.

Fill ‘em all and let god sort ‘em out

Looking at the swapped around datapoints, a pattern emerges. They’re very neatly aligned with the hypothesized effect, and located on the extrema of each distribution. This second point is absolutely critical. The authors argue that even if the data were inadvertently mishandled, the chance that these observations would have been mishandled and none other is extremely low. They run a statistical test (more on that later) to generate a tiny p-value as quantitative evidence that this pattern could not possibly be expected by chance.

It’s not explicitly stated here, but the null model is that the altered rows are drawn at random from all of the possible rows. To start scratching at whether this is plausible, we need to construct something that looks like the dataset not as is but as was. We can do that with a few lines of python, borrowing from the bottom of their blog post’s estimate of what the conditions likely were.

study_one.loc[study_one['P#']==7, 'Cond'] = 0

study_one.loc[study_one['P#']==12, 'Cond'] = 2

study_one.loc[study_one['P#']==51, 'Cond'] = 0

study_one.loc[study_one['P#']==52, 'Cond'] = 0

study_one.loc[study_one['P#']==101, 'Cond'] = 2

study_one.drop_duplicates()

Let’s sort these by condition, but lets hypothetically assume that conditions had text labels in a column at an earlier stage—Control, Top, Bottom. Something mildly interesting happens. All of the out-of-sorts rows are next to one another,

Rows sorted by “Name”, with a secondary sort on the original row numbers

I say mildly interesting, because a lot of this depends on what generated the initial index. It also depends a bit on if and how condition was coded by name, perhaps to keep track of it. If any columns or rows (e.g., dropouts) were removed it’s even harder to trace what happened to get from here to there. Hard to know from where I sit, but it highlights a broader point: Sorting and filter can bring rows closer together, violating the independence assumptions.

Relatedly, consider a hypothetical dataset containing just 2 treatments and outcome variable, sorted by (treatment, outcome). You’ll have the highs from one treatment adjacent in the dataframe with the lows from another. If those cells at the boundary get mangled during data cleaning, all of the mangled cells will correspond with the extrema.

Planawalda

When people are manually editing a dataset, particularly if it’s sorted by a variable of interest, mangling has a better shot at being non-random and adjusting the outcome of a statistical test.

Here’s the rub: Mangling that produces significance will be much more likely to make it into the literature than mangling that erodes an effect. Researchers may be more likely to double check the data if significance is not found. Journals are certainly more likely to publish significant work. Even in a world of randomly mangled data, mangled data would be biased towards significance. We should expect errors in data handling to appear more intentional than expected by chance,if we’re examining the published literature. Strike two against the statistical test.

Finally, and I’ve written about this before, but applying a statistical test because you’ve noticed a pattern in data is effectively embracing QRPs. At best, there’s a file drawer. How many articles, p-curves, etc., do sleuths find and think something fishy is, only to get non-significant results and drop it? Do we really think the false positive rate is zero?

The point of all of this is that we can’t take the statistical test seriously. The null model is simply incorrect, the observations aren’t independent, and we know there is likely a few layers of selection bias. It certainly doesn’t mean there’s a one in a million chance this happened by chance, and honestly, it might not mean much more than the rows were moved (however, for whatever reason) on a sorted dataset.

The test that never was

I’m much more interested in the test that, inexplicably, wasn’t run. Data Colada notes that of the flagged rows, six rows (P#: 7, 12, 51, 52, 92, 101) appear to be out of order. For five of these rows, the movement seems to indicate changes in treatment effect, as the “prior” location was orderly sorted between observations in a different treatment. Although it is buried at the bottom of the blog post, row 92 appears to have been moved but not had its condition changed—chalked up to an accident in the fraud process, incidental, or something weird with CalcChain (we’ll come back to this).

If you think you know what the data looked like before tampering occurred, and you’re alleging that this was done intentionally in service of fraud—wouldn’t it make sense to see if it impacts the results? We can just trivially reassign the treatments as suggested by CalcChain and run a test. If we do, it’s still significant in the same direction (T = -2.1, p = 0.04). The manual alterations to the data were not necessary for the result.

study_one = pd.read_csv('~/Downloads/S1_flagged_2023_06_09.csv')

#Change columns as suggested by Data Colada

study_one.loc[study_one['P#']==7, 'Cond'] = 0

study_one.loc[study_one['P#']==12, 'Cond'] = 2

study_one.loc[study_one['P#']==51, 'Cond'] = 0

study_one.loc[study_one['P#']==52, 'Cond'] = 0

study_one.loc[study_one['P#']==101, 'Cond'] = 2 #Generous here

study_one.drop_duplicates()

#ttest on condition 1 and 2

from scipy.stats import ttest_ind

print(ttest_ind(study_one[study_one['Cond']==1]['Deductions'], study_one[study_one['Cond']==2]['Deductions']))

Some Clarity Now!

Let’s sum things up a little bit.

- The data are clearly manually adjusted and rows have been moved.

- The movements increase the effect along the hypothesized direction.

- Unclear how to distinguish this from selection bias, non-independence of rows in a sorted dataset.

- Of the six rows that had their location moved, one did not have its condition changed.

- One row is duplicated.

- The movement of rows does not impact the direction of the effect or significance.

There are two scenarios:

-

Data were carelessly mangled in handling.

-

Data were intentionally mangled to support the hypothesis.

It is abundantly clear that at 1 is true. I agree with Data Colada’s assessment that someone manually interacted with the data and that rows were moved during this process. It’s more than enough to warrant pulling the raw data, digging in, and seeing what went wrong. I hope/assume Harvard has done this.

The bigger question is 2. The condition swaps do align with the hypothesis and are distributed at the extrema of the distributions. You’d expect something like this with fraud. On the other hand, all of the observations (possibly) sort to a small portion of the dataset, and when sorted they’re not really independent. Suggestive perhaps, but not a slam dunk. We also should expect that when mangled data is found in the literature, it will be mangled in a way that biases towards significance.

The fraud thing also requires accepting one of two kinds of weird possibilities. In the cleanest version, the researcher checked for significance, found it, then went back to move a few rows. Perhaps to avoid being p-curved? It’s not clear why they’d go back. They also seem to have moved one row without changing the condition, perhaps as a mistake? Alternatively, you have to assume they did [something else] alongside the moves and decided to combine fraud tactics for [reasons].

Or these rows were clumped together on a sort and clumsily shuffled in around in excel.

When we talk about fraud, it conjures up the classics. Mixed fonts, obvious distributions being added or obvious skullduggery in the excel sheet. We don’t see anything in shouting distance of this damning here. Instead, we see rows absolutely moved by hand that could well have been clumped and don’t seem to impact significance. We see the rows do swap conditions in a way we’d expect with fraud, but we’d also expect that after a publication filter and sorting. I wholeheartedly agree this is enough to pull the raw data and trace what happened. However, I don’t have a good enough lawyer to feel comfortable alleging fraud based on the content of the blog post alone.

The Bigger Picture(s)

No part of my blog post is intended to serve as a defense of Gino. Harvard has a 1200-page investigation and has put Gino on leave. This broader context cannot be ignored, and it certainly seems indicative of some flavor of misconduct. If I had to make a bet here, I don’t think I’d differ that much from the folks who will be angrily subtweeting me.

The narrower-yet-broader picture regards the blog post in isolation, the evidence it provided, the evidence it didn’t, and the incentives and motivations that fuel it.

I find the use of NHST to establish evidence here peculiar given that the authors published the paper on how flexibility in data analysis can allow researchers to present anything as significant. How many papers were examined? How many datasets were pulled? How many authors? Was the pattern noticed before the decision to run the t-test? Is this HARKing?

In the second blog post, why choose a t-test when the variance for one category is zero? What other tests could have been chosen? Aren’t small-N studies unreliable? What’s the power analysis for N=8, and would you run the test if you had conducted a power analysis? None of the assurances and rigor we increasingly expect with published literature can be found here.

It’s also quite telling what tests they didn’t run. Neither in this blog post, nor in the subsequent one, did they check to see if the manipulations they identified impacted the findings. Although they do not explicitly note it, the results they present in Blog Post #2 differ from the original study in that they group two of the conditions. Even dropping the suspicious observations, the test as they implemented it remains significant. It likewise remains significant for the comparison of one of the two conditions when pairwise comparisons are made. There isn’t clear evidence that the suspicious rows here were necessary for significance.

Of course, it isn’t definitive, but it would certainly be a very big piece of the puzzle. If, in both cases, it made or broke significance—that would be telling. It’s very hard to believe that in two years they didn’t think to. Given that in both cases, the effect persists, did they just bury these tests in file drawers?

Similarly, there was not even a whiff of an attempt to consider alternative explanations. It’s obvious that findings from the top of one distribution and the bottom of another can be aligned in a dataset if the dataset is sorted on the observable. There’s also very little effort put into why the observations can clump in a sort—something that doesn’t seem particularly necessary for fraud but is pretty essential for earnest mangling.

Moreover, in discussing what points were swapped around, they bury the fact that one of the data points didn’t change condition at all. This is not something you’d expect with fraudulent data manipulation. It kind of makes sense for mangling. Why dark-pattern this finding away?

In totality, the blog post only presents evidence in favor of these rows being switched due to fraud and either buries or simply fails to mention any competing possibilities. Even if you think they’re far-fetched, they’re plausible, and it doesn’t hurt to bring them up if only to point out why they’re wrong.

DC also uses inappropriate statistical testing to add a bit of quantitative dazzle, without considering if the null model is appropriate or potential sources of bias. Whether or not fraud happened, one thing is clear: The blog posts are trying to convince you that it did and unwilling to even perfunctorily consider anything nuanced or conflicting.

Make no mistake, this is persuasive writing—not a neutral investigation.

Clout and Consequence

Of course it is.

The authors’ careers over the past decade have been centered around developing and implementing methods to find things “wrong” in the literature. That’s probably how you know them. They have every incentive to find things that are wrong. This is no different from honest researchers who have every incentive to find that the location of a signature implausibly impacts honesty. In both cases, finding what you’re looking for renders clout and prestige. Why else rush to release blog posts after a journalist scoops you, dripping one by one as though it’s some sort of Q-Anon drop?

This is the reason we need to be as critical and skeptical of the critiques as we are of the literature itself. We need to hold both to the same standard of rigor, from pointing out inappropriate use of NHST to noting excluded conflicting evidence and failure to consider alternative explanations. The background and broader context of an investigation don’t matter. We need to have standards.

We need standards because these types of blog posts and Twitter threads have consequences for the mental health and careers of people who are targeted. If we let those standards slide in a context where misconduct seems likely, we can let them slide anywhere. What if you, or your student, years ago sorted and mangled a dataset? Wouldn’t you want to be emailed and given the chance to share the raw data and trace the error before being accused of fraud? Shouldn’t the accusers check if the mangling impacted the results? Should they consider alternative explanations?

Why don’t we have the same rigor for critics and the critiqued? How can we reconcile that widely-held beliefs incentivize rendering most of science incorrect with an assumption that Data Colada and other sleuths bat 1.000 using the same methods? Where are the papers on the false-positive rate for data sleuthing? What blog post shows that someone else’s career-ending blog post was flawed? Why is it okay to use whatever statistical test on N=8, without preregistration or power analysis, on whatever dataset and allege fraud? How big is the file drawer?

The “Data Police” metaphor is imperfect but apt. Police are motivated to find evidence and put bad guys away. It often leads to biased policing, looking where they’ve looked or where their biases compel them. Sometimes, innocent people go to jail. With the law, we try to buffer against this with defense attorneys, formal court proceedings, juries of our peers, presumptions of innocence, and internal affairs to investigate police behaving poorly.

As flawed as our criminal justice system is (boy, is it), it at least has these mechanisms in place. No similarities exist in our policing of the literature. Any critique of Data Colada or similar sleuths leads to a flurry of QTs, sub-tweets, and replies. I fully expect to mute my mentions tomorrow. People expressing discomfort the other day were subjected to racism, misogyny, mockery, accusations of fraud, and endless sealioning. Almost every post noting concerns had a deferential line of roughly “not saying anything bad about the data police, but.” It’s not deference, it’s fear. There’s just no room to consider anything other than the persuasive pieces written by people with an incentive to write them.

Maybe we should look at the bigger picture and ask what the externalities here are, and how they might be mitigated?

Summing up? Sure, I think the data looks fishy, and absolutely, this needs a thorough investigation. I don’t think it needs a motivated blog post trying to convince the reader that doesn’t even pretend to engage with nuance.

coda: I’m going to use the bottom of this post to reserve the right not to respond to angry replies that haven’t read this far and posted a screenshot of the dataset open on their computer. I’m also going to note that I wrote this inside a couple hours, and if you find an issue or mistake… my dms are open.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: