I did not want to write this blog post.

The Preregistration Revelation

I did not want to write this blog post. I hate when science gets resolved by blog and thread. This is why I emailed the authors in November of last year. I shared very detailed concerns and offered to walk them through those concerns so they could retract on their own terms. They declined. Instead, I got the runaround familiar to anyone asking for data available upon request. This was frustrating but not yet alarming. What really concerned me was this post by Brian Nosek:

To anyone reading, this seems like a quite reasonable narrative. After all, it isn’t a grave sin to forget to preregister a descriptive analysis or two. From my perspective, it was quite different. I had emailed the authors and provided a very clear outlined draft and code comparison indicating that virtually none of the analyses matched the preregistration. One or two analyses is a mistake, the entire main text is a problem. Brian had to have known the issues were much more substantial than he let on, and posted in a way that minimized the seriousness of the issues.

I still did not want to write this blog post, but I no longer felt confident the authors would earnestly evaluate the concerns. I wrote a dozen pages carefully detailing the issues and privately shared them with the editors. This was entirely distinct from the Matters Arising. Berna was not involved. I asked that my role in sharing these concerns not be made public, although said it could be shared with the authors to facilitate resolution. I thought perhaps the gravity would convince them to engage with the concerns and voluntarily retract. They did not. They did, however, upload a large trove of historical documentation as part of the investigation I was not privy too.

Examining these new files confirmed my concerns and raised many, many more. We wound up way past a simple issue whereby they forgot to preregister some or even all analyses. I felt compelled to send an additional write-up of my findings to the editors. For those unfamiliar with the process, I had heard nothing back about anything the authors or experts reviewing the concerns had said or contributed. Late this summer, I was informed that the investigation had concluded and they found my concerns were well-founded. The paper was retracted not over the issue of preregistration, but over a much deeper set of concerns that raise serious ethical questions and most importantly undermine the claims of the paper.

At this point, I thought surely the authors would own up to their mistakes and I would not have to write this blog post. All along, I have hoped the authors would acknowledge their mistakes and move on. I held out some shred of belief that people who have built careers on honesty, transparency, and openness could be honest, open, and transparent. I was naive.

They are misrepresenting the reason for retraction. They’re presenting it as a minor procedural issue with a sentence describing what was preregistered, and some deviations they failed to disclose. Worse, people on social media are believing this and applauding them for their honesty and contrition. Yet this is all bullshit and spin. The paper would not have been retracted, nor would I have raised concerns, if this was the only issue. It wouldn’t have taken 10 months and twenty pages of documentation.

Mostly, I don’t have the time to write this. I work a 9-to-5, am writing a book, and have science to do. My website broke so I’ve slapped it up temporarily on a placeholder website… I don’t have time to fix it. I suspect the editors, my co-authors, reviewers, and ethics board members who spent countless hours trying to understand what the authors did and correct the record felt much the same. Brandolini’s law in full force. I am writing it because it is only fair to their time to share this, given the authors unwillingness to portray what happened honestly.

Because I’m short on time you’ll find typos. You may find errors. You may need to dig around on their OSF to verify things. Most of the relevant files can be found in this zip which tragically I cannot link to individually. If you’re wondering whether you can trust this, I can safely say this is a subset of the things I shared with the editors and I have heard and seen nothing from the authors or team at NHB to suggest anything I raise here is incorrect.

Without further ado

Calling Bullshit

If you read the retraction note, the editors do not mince words about why this study was retracted:

- “lack of transparency and misstatement of the hypotheses and predictions the reported meta-study was designed to test”

- “lack of preregistration for measures and analyses supporting the titular claim (against statements asserting preregistration in the published article)”

- “selection of outcome measures and analyses with knowledge of the data”

- “incomplete reporting of data and analyses.”

How could a sentence describing all analyses as preregistered result in anything beyond the 2nd reason given? Why would a journal make such strong statements over a sentence and a few deviations? No paper has ever been retracted—if even corrected—for issues that small. Let’s go through these one by one, as these reasons are what the authors have long described as questionable research practices (QRPs).

The first is Outcome Switching. The authors switched the decade-long-planned outcome of the study from an null finding for a supernatural phenomenon to one on replication discovered after analysis that affirmed their long-standing advocacy and was marketed to funders.

The second issue is Falsification. They repeatedly—even in the note they just published—made false claims about their research process. We often think of falsifying data, but false claims about study methodology–including preregistration—is falsification.

The third is HARKing. They analyzed their data, noticed a descriptive result and wrote the paper around it. They conducted statistical tests after having viewed the data that they are still claiming were preregistered (see below).

The final issue is selectively reporting of analyses and data. They have utterly refused to provide essential insight into their piloting phase, despite the issue having been raised at least four years ago in peer review and again during the investigation. The relevant repositories remain private.

If you simply read the retraction notice the journal put out rather than the authors’ statement it is clear the paper was rejected because the authors were found to have engaged extensively in QRPs. Of course questionable research practices are questionable but when a group of experts on the subject engage in them repeatedly to push a claim they fundraise on it makes you start to question. It is very important to realize that, much like a business school professor selling books based on fraud… several key authors have every reason to generate and protect this finding.

Feeling Not so HOT (Honest, Open and Transparent)

In the authors’ recently released OSF post mortem, Brian seems to suggest that the problems mostly surrounded a single line in the paper. Tellingly their explanation involves no engagement with the substance of the retraction notice or the matters arising. What possible reason, other than obfuscation, would there be not to even address the journal’s decision as they wrote it? Instead, he focuses on something we mention only in passing. Something much less ethically fraught that he has been saying since November of last year. The inaccuracy of this line in their paper:

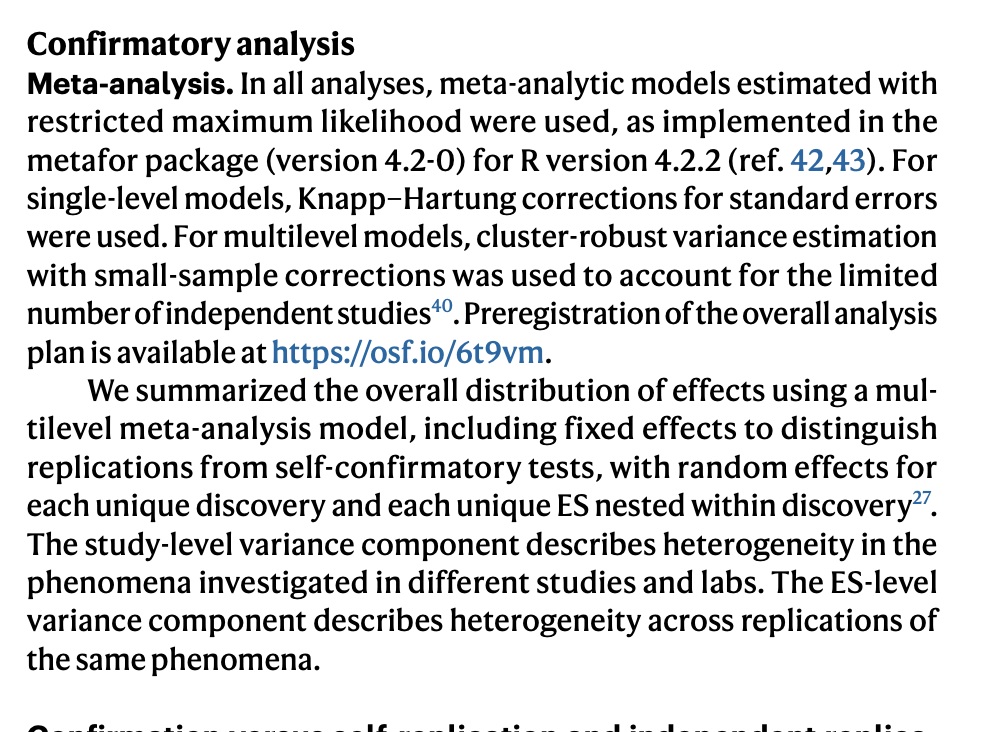

“All confirmatory tests, replications and analyses were preregistered both in the individual studies (Supplementary Information section 3 and Supplementary Table 2) and for this meta-project (https://osf.io/6t9vm).”

Read the authors’ post mortem in contrast with the journal’s exact language for why the retraction occurred. It is downright deceptive to describe the retraction as primarily a result of this sentence. The issue they highlight as the cause for retraction is only a minor point that could have been fixed with a correction. No one, myself included, felt this line alone was cause enough to retract from the beginning. It would not have taken ten months and four reviewers to sort this out. I understand that if authors disagree with the retraction—most authors of most retractions do—yet this is no excuse for failing to engage substantively with the journal’s rationale and create the impression the cause was quite different.

The authors post-game write-up, along with spinning an offer to submit a fresh manuscript to fresh peer review as an R&R has been very effective spin. Commentators on twitter appear to think this just isn’t a big deal. Everyone is making a mountain out of a molehill and the authors are setting a good example by “retracting, revising and resubmitting”

What is striking is that even now the authors are choosing to obfuscate what they actually preregistered. Later in the note, they explain how this specific language came about and highlight that elsewhere they’ve described things accurately:

“Many” might leave you with the impression that this section accurately described the preregistered analyses. Nope. Let’s take the very first analysis in that confirmatory analysis section. It describes a multi-level meta-analysis that was coded up by James Pustejovsky:

You can even check out the pre-registered analysis code which describes this analysis as exploratory. As a fun aside, this preregistered code was developed by a paid consultant they hired to provide feedback on the pre-registration and develop the pre-registration code. There’s a whole version history ostensibly created without access to data leading up to the presentation of results at Metascience 2019. Importantly, none of this code was released with original manuscript and only came to light after I raised the issue when sumbitting my concerns for investigation. So somehow in addition to forgetting what exactly they preregistered when writing it up, they forgot entirely that about this whole side-plot with a consultant they paid (who became a co-author) and just neglected to upload the code which would have made it much more obvious that the analyses were not preregisterd. What bad luck!

Returning to the meta-analysis.

You know how we really know this meta-analysis is exploratory though? Because an old version of the paper clearly indicates they added this analysis in March of 2020 (“Decipfhering the Decline Effect P6_JEP.docx”)—well after Schooler gave a talk on a preliminary analysis of the data. Conducting an analysis after having analyzed the data and observed pattern is, by the authors own definitions, not a confirmatory test. It’s a QRP to present it as one. It’s worth highlighting that this meta-analysis is different from their analysis of variation in replicability across labs across labs, which their correction notice indicates was also exploratory and relabeled as confirmatory…

Hell, later in their published post-mortem they (maybe?) allude to this analysis not being preregistered by saying that “some sensitivity and heterogeneity analyses” were not preregistered. But that doesn’t fix the earlier language which seems to imply this section described the preregistered analyses. Perhaps what they were thinking of was the section of their supplement called “pre-registered analyses” which does describe the preregistration accurately. Unfortunately this is within a section also called confirmatory analyses which misleadingly claims that the replication rate and the exploratory-turned-confirmatory lab-specific variation were confirmatory. Why does this section differ from the main text? Who knows? Might be hard to keep your story straight about what you preregistered if you’ve abandoned your prereg long ago.

All this is to say that if they mistakenly described what was preregistered, they did it in three distinct places and forgot to upload the code corresponding to the actually preregistered analysis which they describe accurately in the supplement. None of the authors managed to notice this, or the fact that the paper contained multiple inconsistent descriptions of what was preregistered. I don’t care if they had a secret desire to analyze replicablity, in what world do more than a dozen experts–two of whom built platforms to make it easy and careers on encouraging it—forget what they preregistered this severely.

Hanlon’s razor is having a hard time with this one. I really don’t know if it’s more alarming if they intentionally mislead the readers or if a team of experts on preregistration can’t even notice if the two sections labeled confirmatory analyses are consistent—and match what they paid a consultant to develop. Unethical behavior here could be limited to this paper or maybe the papers of a few key authors. Yet if this is the extent to which this group of experts can check their own manuscript in revision for three years for internal consistency… even after the paper has been retracted… there is a mountain of literature someone needs to go back and check.

It is not just about the preregistration

Hopefully the above makes it dreadfully clear that the authors are either unable or unwilling to be honest, open and transparent about what they preregistered, even now. Yet if this had just been a need to clarify which analyses were exploratory, we would have seen a correction in January and this whole thing would be a distant memory. The paper was retracted for many more reasons, a small subset of the easiest to explain are described below.

Outcome Switching and lying by omission.

One of the key reasons this paper was retracted is that the authors do not accurately describe their original, pre-registered motivation for the study. It is one thing to forget to preregister but it is entirely different to simply switch outcomes and pretend you were studying that thing all along.

Stephanie Lee’s story covers the supernatural hypothesis that motivated the research and earned the funding from a parapsychology-friendly funder. Author Jonathan Schooler had long ago proposed that merely observing a phenomenon could change its effect size. Perhaps the other authors thought this was stupid, but that’s a fantastic reason to either a) not be part of the project or b) write a separate preregistration for what you predict. We can see how the manuscript evolved to obscure this motivation for the study. The authors were somewhat transparent about their unconventional supernatural explanation in the early drafts of the paper from 2020:

“According to one theory of the decline effect, the decline is caused by a study being repeatedly run (i.e., an exposure effect)25. According to this account, the more studies run between the confirmation study and the self-replication, the greater the decline should be.”

This is nearly verbatim from the preregistration:

According to one theory of the decline effect, the decline is caused by a study being repeatedly run (i.e., an exposure effect). Thus, we predict that the more studies run between the confirmation study and the self-replication, the greater will be the decline effect.

It is also found in responses to reviewers at Nature, who sensed the authors were testing a supernatural idea even though they had reframed things towards replication by this point:

“The short answer to the purpose of many of these features was to design the study a priori to address exotic possibilities for the decline effect that are at the fringes of scientific discourse….”

As an aside, it’s wild to call your co-authors and funder the fringes of scientific discourse. Why take money from and work with cranks? Have some dignity. Notably, perhaps to keep the funders happy, they were generous enough to keep this idea around in the in the name of their OSF repo and the original title:

The replicability of newly discovered psychological findings over repeated replications

It’s also in their original discussion:

Importantly, the number of times the initial investigators replicated an effect themselves is not predictive of the replicability of the effect by independent teams (Kunert, 2016).

This utterly batshit supernatural framing erodes en route to the the published manuscript. Instead, the authors refer to these primary hypotheses that date back to the origin of the project as phenomena of secondary interest and do not describe the hypotheses and mechanisms explicitly. They refer only to this original motivation in the supplement of “test of unusual possible explanations.”

Why not? Well, no need to speculate. The authors say exactly why in their response to Tal Yarkoni who asked them in review at Nature to come out and say it if they were testing a supernatural hypothesis. They decided to just change the message of the paper.

“As such we revised the manuscript so as not to dwell on the decline effect hypotheses and kept that discussion and motivation for the design elements to the SOM.”

It’s fine to realize your idea was bad, but something else to try bury it in the supplement and write up a whole different paper you describe in multiple places as being preregistered and what you set out to study. Peer review is no excuse for misleading readers just to get your study published because the original idea you were funded to study was absurd.

Nevertheless, when you read the paper, you’d have no idea this is what they got funding to study. Their omitted variables and undisclosed deviations in their main-text statistical models make it even harder to discern they were after the decline effect. They were only found in the pre-registered analysis code which was made public during the investigation.

In distancing themselves for two of the three reasons they got funding they mislead the reader about what they set out to study and why. This isn’t a preregistration issue. This is outcome switching, and lying. It’s almost not even by omission because they say it’s the fringes of scientific discourse but it’s the senior author on the paper!

The third reason they note in early documents, most closely aligned with their goals is the “creation of a gold standard” for conducting research. While this very much aligns with the message of the paper, it is really important to note that the evaluation criteria boils down to if they fail to observe the supernatural effect they’ll have succeeded. It’ like arguing that if I don’t find a unicorn today, I’ve solved cold fusion. See our matters arising if you want to sort out why this is bad logic.

The authors seem to indicate in their post-mortem analysis that they had planned this framing and analysis all along. If so, it’s damn surprising that none of this came up in the investigation. Why not include a link to literally any evidence of the claims in this paragraph? You think if you’re on the hook for outcome switching and HARKing you could toss in a URL to provide evidence to the contrary.

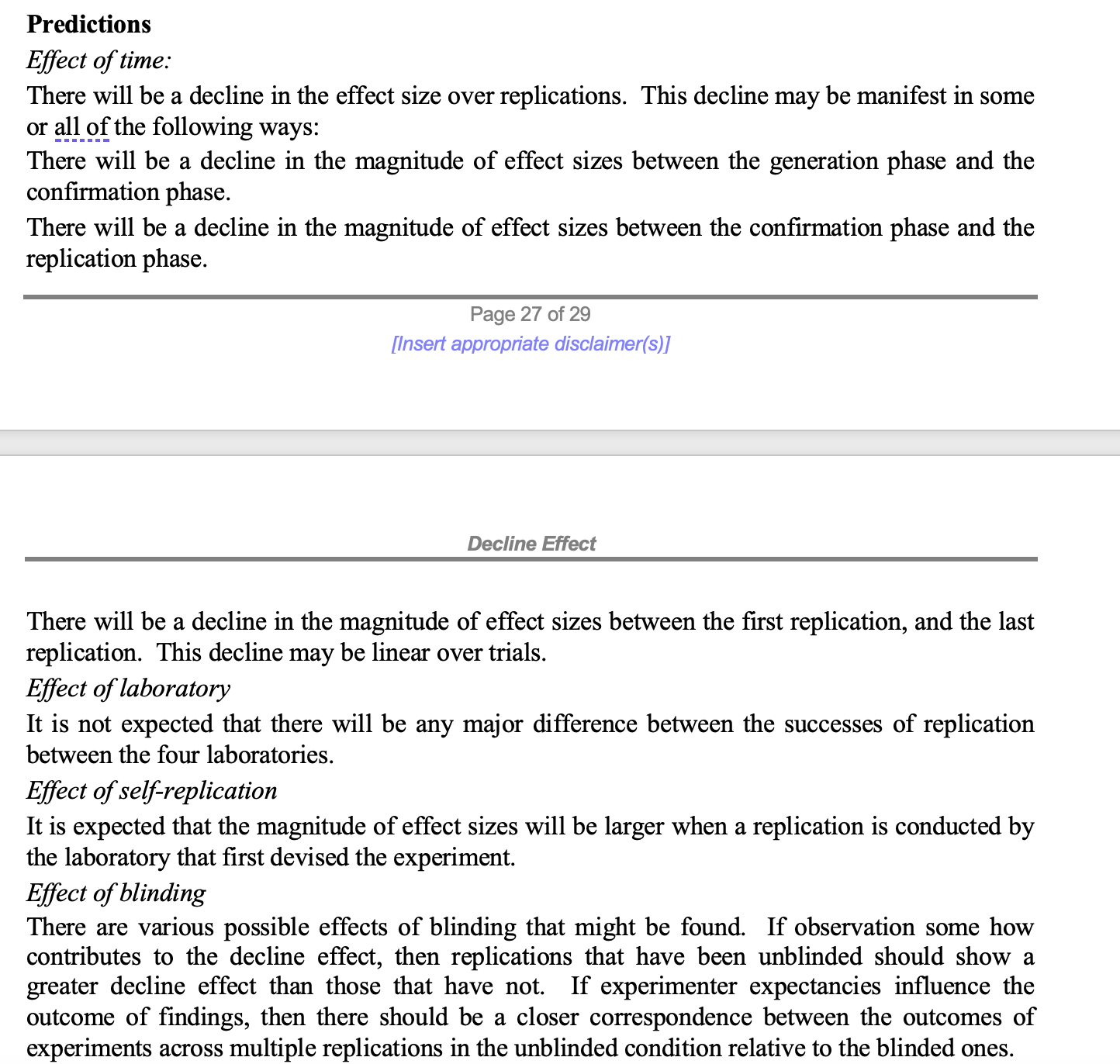

Perhaps they’re referring to their operations manual but I certainly hope not. There is no plan in that document that matches the description above. If you think the decline thing is absurd and you’re just doing this to study replication… why not mention what you’re going to measure it in any of the dozen versions of the operations manual or the two pre-registrations? Instead, Here’s their early predictions, make of them what you will:

If there is some time-stamped documentation that clearly states a desire to measure replicability—much less how they’ll do so—I cannot fathom why they did not produce it during the investigation or when I reached out in November. Perhaps it exists, but other evidence suggests otherwise. What evidence? Well, I’m glad you asked.

HARKing, Hacking and Cherry-Picking

What really chaps my ass about the tweet indicating this is a procedural error is that it somehow ignores their decade of arguing that failing to preregister risks analyses that are conditioned on chance patterns in the data. If you alter your analysis in response to data to achieve a desired result, that result is less trustworthy. Isn’t that the whole story? And sure, exploratory research has value but repeatedly claiming your exploratory data-dependent research is confirmatory is a big, big problem. As Nosek 2018 put it:

“Why does the distinction between prediction and postdiction matter? Failing to appreciate the difference can lead to overconfidence in post hoc explanations (postdictions) and inflate the likelihood of believing that there is evidence for a finding when there is not. Presenting postdictions as predictions can increase the attractiveness and publishability of findings by falsely reducing uncertainty.”

By extension, repeatedly claiming that you’re doing prediction when you’re doing postdiction misleads your audience into believing you found more than you did. It’s deceptive and it is wrong.

So did they alter their analysis in response to data? Sure seems like it.

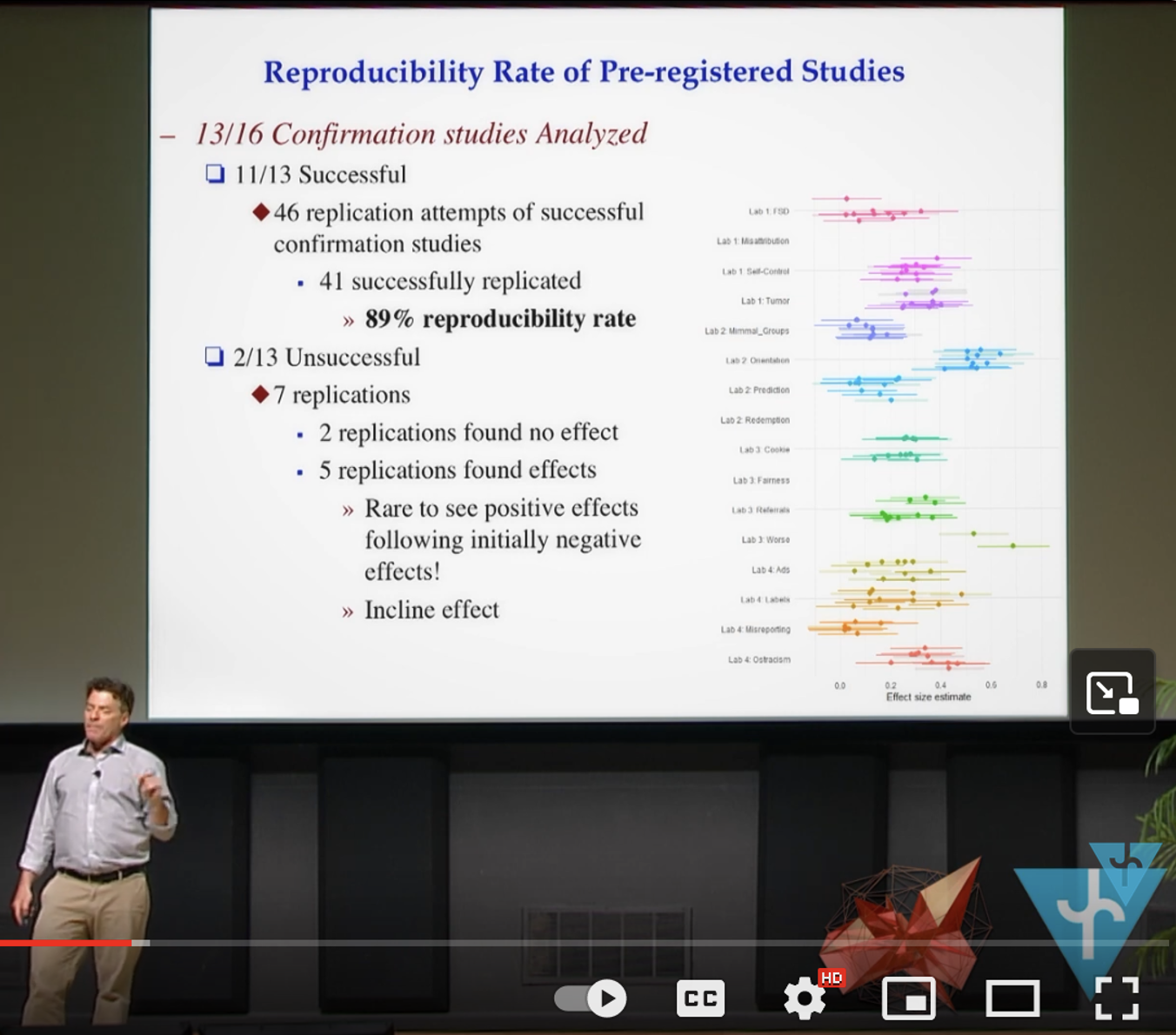

Replicability was not found in the original preregistration. Nor is it found in the analysis code dated 09/03/2019. The first mention of estimating replicability was during Schooler’s talk on 09/05/2019, which estimated replicability as the proportion of significant results among the studies with significant confirmatory tests.

As with past work, they do not emphasize this rate for null confirmatory tests. Instead, they seemed surprised by the rate of significance for null findings. Schooler frames it as an incline effect.

Between Schooler’s talk and the first draft of the write-up they wind up with this abstract and general set of conclusions from their analysis:

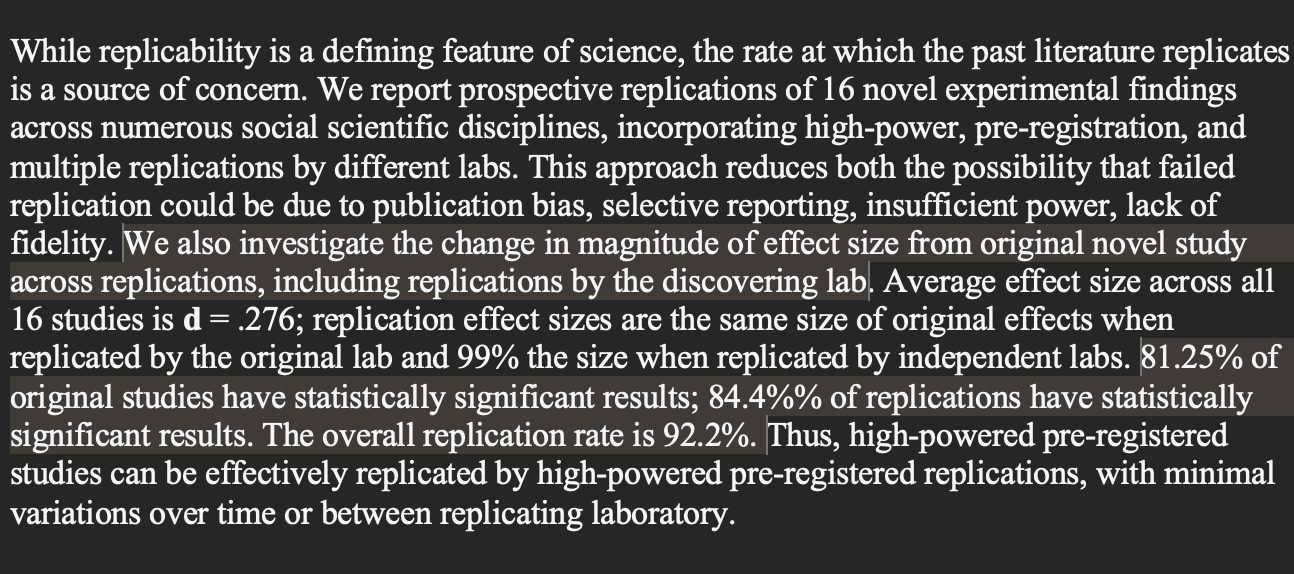

This abstract for the earliest version of the manuscript states the replication rate is 92.2% (59/64) based on a definition that considers null replications of null confirmatory studies as “successful”.

There are a few things to note. Their original conclusion is that “high-powered pre-registered studies can be effectively replicated by high-powered pre-registered replications”. This makes sense because they are replicating the confirmatory studies in the original drafts framing—which were high powered. In the published version they’ve broadened this conclude that “This high replication rate justifies confidence in rigour-enhancing methods to increase the replicability of new discoveries.” Where did that framing come from? If this was the goal all along you’d think whoever wrote this draft would be aware.

Their definition of replicability used in the final version is not referred to here as replicability but simply statistically significant results. The reason they’re not calling this replicability is because initially they’re considering the outcome of the confirmatory study when estimating replicability. This accounts for the “highly powered pre-registered studies” language in their original abstract.

The trouble is that this 92.2% appears to be a mathematical error, as it includes 47 of the 52 replications of significant confirmatory studies and appears to include all 12 replications of null confirmatory studies regardless of outcome. When corrected, this definition would produce a replicability rate would be 79% (51/64). This would be considerably lower than this drafts’ chosen method of calculating statistical power (~100%), and lower than replicability in the published version (86%). It would also be lower than the highest estimates from the literature cited in the initial version and later omitted for reasons unstated (11/13 or 85% from Klein et al 2014). These are the two arguments they based the title on and they fall apart once you fix this little calculation error.

But that shiny 84.4% rate of significance is sitting right there! So now, it’s no longer the confirmatory studies they’re replicating but the predicted direction from the pilots they refuse to make public. This gets around the “incline effect” and awkwardness of cases like the Redemption study’s apparent direction reversal. The trouble is that this is not a metric anyone would plan a priori because it is far too sensitive to the base rate. Imagine they had only found 8 “true” findings. 100% significant results in replication for these true findings and 100% replication nulls for the null confirmatory studies. Their measure would indicate 50% replicability—the same as they say is typical in the literature. When you have perfect agreement between statistical decisions arising from replications and confirmations this metric just winds up just measuring the base rate. If it’s 10%? Replicability is 10%. This measure only indicates high replicability because the base rate is so high.

Ok, but its not just this choice of measure that is a problem. As versions go on, they do a few things to bring their replicability above their power and the replicability in the literature. First, they revise their estimate of statistical power in a very strange way such that statistical power is zero when the sign of confirmatory test differs from predicted value even though the tests are two-tailed and the theoretical minimum is 5%. They lump in the near-1.0 statistical power estimates for significant confirmatory studies with this weird, at times zero, measure for null studies and goose statistical power down below their absurd and clearly opportunistic replicability estimate. Taken together, their claim that their rate of replication exceeds the theoretical maximum only arises as a result of jointly evolving their estimate of power and replicability. This is hacking statistics to make a claim.

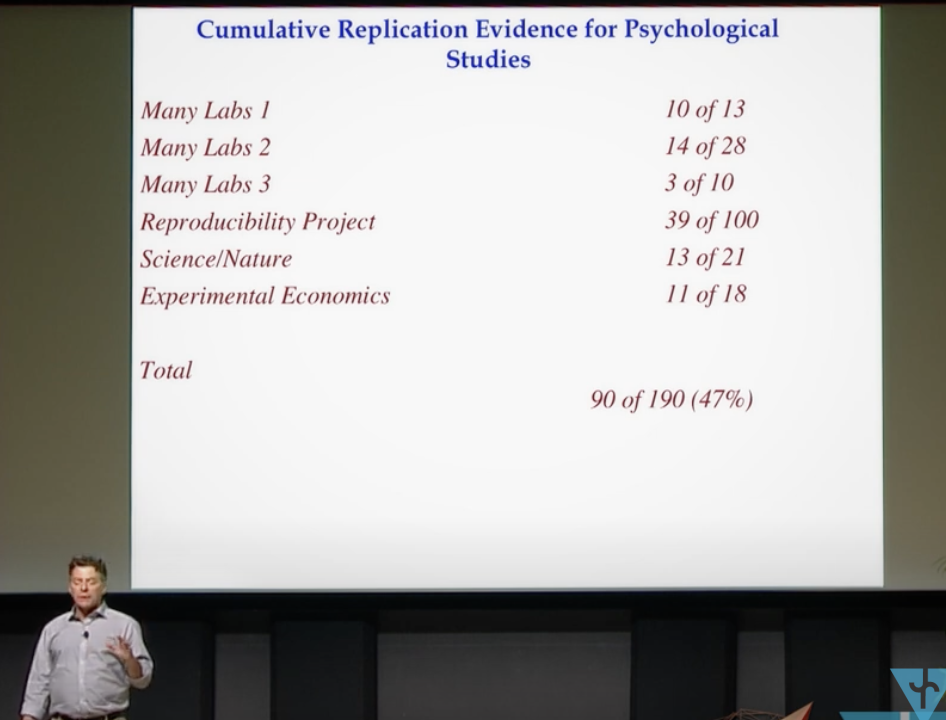

Finally, they even alter what they define as the literature-wide rate of replicability they compare against. A key claim is that they observed high replicability and the literature has not. In the main text cite a range of replicability (30-70%) which they seem to average at 50%. You might think the approximately 50% here is just the halfway point between 30 and 70. Nope, the talk by [Schooler] lays out their original math.

There are plenty of problems with this, not the least of which is that several of these studies involve non-random sampling frames and the estimate of replicability is a result of the chosen mix of well-replicated and novel findings. But the real rub is Many Labs 1. 10 out of 13 is 77%. In reality it’s 11 out of 13 or 85% using their criteria of significance. Ooops, high replicability was achieved a decade ago replicating the open literature. Can’t have that.

From the initial analysis to subsequent versions, they cite ML2 and ML3 but all of a sudden leave out this study which would have undermined that claim they were higher than the disappointing range in the literature. Their 92.2% might have looked better, but the 86% is right there with it. They also opt to leave out Soto 2019 which has 87% successful replicability. It’s hard to make a claim that rigor-enhancing techniques are necessary for replicability when two other studies have replicated portions of the literature at similar rates which most assuredly did not embrace these techniques in discovery. Perhaps they didn’t know Soto’s work, but they certainly knew Many Labs 1. The two projects shared authors. If there was some justified reason for selectively excluding mid write-up the one study in the literature that makes it impossible for them to make the claim… that would be a stroke of luck. They seemed to have invented the informal comparison equivalent of selective removing of outliers. Maybe they’d argue it’s not a QRP because it isn’t a formal statistical test, but that didn’t stop them from anchoring the titular claim on this comparison.

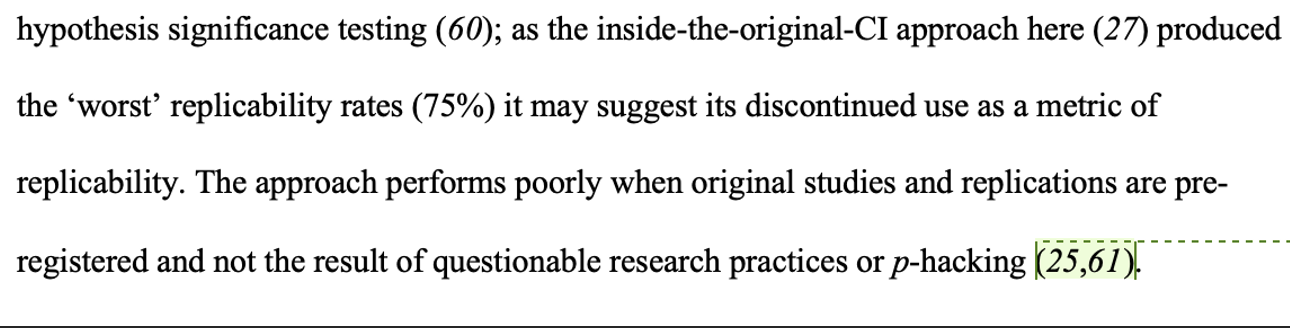

So they cherry-picked their point of comparison, selectively omitted two conflicting points of comparison from their original framing, and hacked their estimates of power and replicability to be near one another. We really don’t have to speculate that they cherry-picked. They come out and say the quiet part loud in an earlier draft. Here, their 75% confidence interval is lower than their their other metrics and they suggest that because it should have been high it should no longer be used as a metric.

Null hacking??

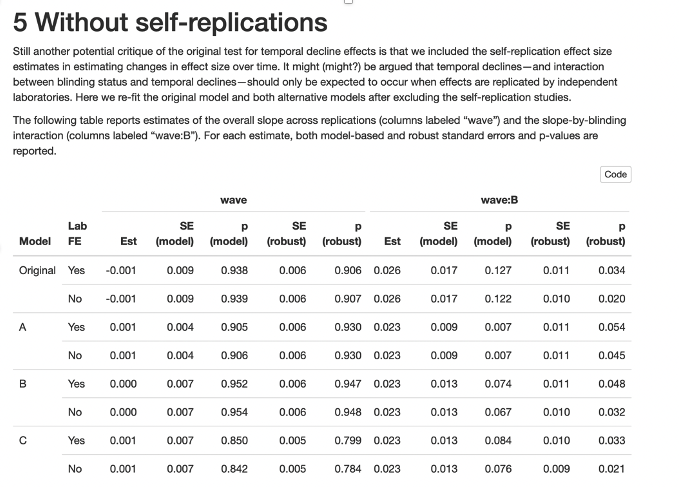

During the investigation, the authors uploaded an apparently undisclosed sensitivity analysis of some sort (Decline effects/Decline effects - temporal decline and blinding.Rmd). The file appears last modified on March 15th, 2020 shortly after the earliest provided draft of the paper (March 14th, 2020). This code involved four different specifications from the preregistered model, evaluated in various ways: without the blinding effect, without self-replications, independent replications only, and controlling for independent replications.

Although these analyses are not described in the published version, they appear to explore the possible model space to (generously) probe whether the results are consistent across model specifications. In the variation that ignores self-replications, the authors do find an interaction effect between wave and blinding that is significant and consistently so across model specifications (see below). It is unclear why the model space was explored so thoroughly and yet these analyses (and their conflicting results) were not included in the write-up. It also seems like there’s gotta be some name for running a model a bunch of different ways like a specification analysis and selectively presenting the null results. Oh wait, that’s Null Hacking (Protzko 2018)

Omission

Frankly, all of the above could probably be weaseled around. Is it really a formal analyses? These are just descriptives. Everyone engages in QRPs so what’s the big deal here? Maybe the results are still good? Isn’t this obviously true so who cares if the authors embraced all of those things the authors are arguing need to be eradicated for science to work…

But here’s the key reason the findings couldn’t be trusted, even if you think everything above is a nothing-burger. It requires the tiniest bit of causal inference understanding, specifically that causes occur before effects.

The paper contends that the authors discovered a set of highly replicable findings when using rigor-enhancing best practices. Because the discoveries occurred during the piloting phase, this can only be logically true if they followed the practices in piloting. Practices observed in replication cannot have caused the set of discoveries which were committed to before confirmation and replication.

You can read more about the problem in depth as written by Hullman, who reviewed the Matters arising and the concerns. Tal Yarkoni, reviewing an earlier submission at Nature, pointed out the need to be transparent about the piloting process 4 years ago. Despite the centrality of the piloting to the effects discovered, the authors have refused to make information about pilots openly and transparently available. They have been silent in response to both Tal and Jessica’s concerns.

As you read the paper, ask yourself the following questions:

- Did they verify all pilots were pre-registered and conducted without deviations?

- How many hypotheses were tested per pilot?

- Were they allowed to enter exploratory, post-hoc analyses based on trends in the pilot?

- What were the actual sample sizes of the pilots?

- Etc…

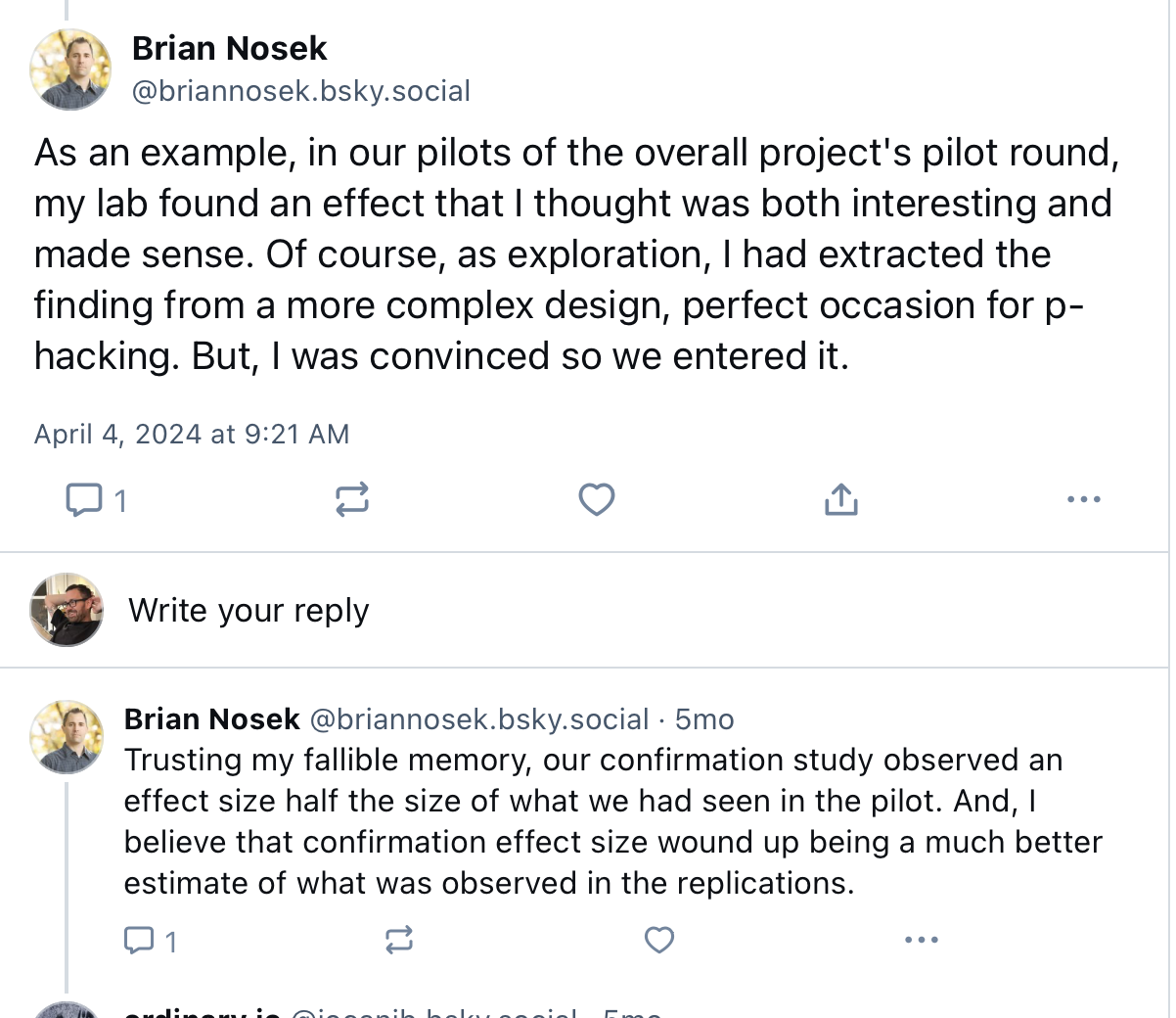

Why is there so little clarity on the process that caused the discoveries? What few pilots I’ve found by weird google searches suggested they were free to test a bunch of outcomes and pick one of the hypotheses to pull forward. It’s clear they didn’t embrace the practice of large sample sizes (1500) in piloting. Worse, it seems they were free to embrace analytic flexibility during pilots as per a post of Nosek’s. He seems to suggest that rigor-enhancing best practices were not strictly required during the pilot–contrary to claims in the paper. We also get an indication that effect sizes declined where we’d expect them to and the authors really didn’t feel the need to mention this in the write-up.

Think about this for a second. If they found 16 hypotheses dredging out significant findings from some unstated number of n=200 experiments, committed to replicating them, and got 80% replicability or whatever… it implies that best practices are very much not needed to find replicable results. It seems you can data-dredge and hack significant findings from pilots at n=200, publish them and rest assured the replication crisis is over if the replicators use large sample sizes.

This is a Huge question on which the entire paper depends. Tal Pointed it out in his review. James, their hired consultant, brought up the pilot selection problem in comments on drafts of the original preregistration in ~2018. Why ignore your hired statistican, reviewers, and the concerns that might retract your paper and still refuse to click “make public” on those pilot repositories? Their post-mortem suggests they’re analyzing the data, they must be organized somewhere, so why are they so reluctant to make them openly available?

This was a key reason for retraction, as indicated in Hullman’s review. The authors have been aware of the concerns for 4-6 years. It was emphasized in our matters arising in raised in the concerns that prompted the investigation. Against this backdrop, it seems pretty damn misleading for their post-mortem to say:

Also, our findings spurred interest in what occurred in the pilot phase of the project. We are likewise quite interested to learn more about the pilot phase.

It is very difficult to square this with openness, honesty and transparency.

Putting it all together

As I said at the outset. I had no desire to write this blog post. I didn’t want to wade into all of this. Their OSF is such a mess that getting claims straight and conveying them to others is a nightmare. Many of the links above will just open a massive zip file you’ll have to navigate to find the corresponding file. Good luck, go with god. Other parts of their repo including pilots of are unlinked and can only be found by searching on the internet archive, finding a registration and working your way back up—often to a still private repository. And despite the fact that embargos for many pilots should have lifted if they were actually preregistered, I can’t find most by searching in this manner. At times, preregistration seem to be little more than word documented uploaded to an OSF that they could easily remove or edit. Sometimes it’s just a description in a wiki.

I have little doubt some will remain unconvinced because this post was tl;dr and the files are td;dr (too disorganized, didn’t read). I expect the authors and probably Lakens to try to seize on a thing or two I got wrong somewhere in here because the repo is a mess and they haven’t addressed any of these concerns. The inevitable bad faith response this will trigger is one of the very many reasons I did not want to write this post. I hate looking forward to some long screed of a blog post where a red square says “Oh but they measured replication in the only logical way to do so, I am not very impressed by Joe’s scientific abilities” or whatnot. Perhaps the authors saying they appreciate my concerns but disagree and will provide documentation. Same thing I’ve been hearing since November.

All this is to say if I’m wrong about anything I’m happy to correct or amend. But even if one or two things could be written or framed differently, a lot would have to be wrong for it to meaningfully change the story. Still, if you doubt what’s above, rest assured that this is an abbreviated version of 20+ pages concerns I raised which were independently verified by a ten month investigation involving numerous domain and ethics experts.

Whatever your thoughts, ask yourself: How many changes, updates, switched analyses, outcomes, rewrites would it take to call this more than just an “embarrassing mistake”? How many mistakes are we allowed until we cannot shrug them of brazenly? At what point should we be held accountable for allowing mistakes to accumulate over years despite repeated feedback? How many “oopsies” would it take before we interpret their “aw shucks” posts in the last few days as lies intended to cover up their actions?

If it’s fewer than I’ve espoused here, I’m happy to share plenty more. This post contains what I consider the bare minimum to convey that they are not being honest. The authors forced my hand, after nearly a year of avoiding making this all public. I could have written this post at any time, if my goal was just to sling mud. Yet their utterly misleading description of why the paper was retracted undermines my attempting to address this through the proper channels. It undermines the hundreds of hours experts spent unravelling this shit when they could have been doing literally anything else. Despite the extra work in comparison to slapping up a blog post, I reported these concerns formally, privately, and quietly because I really did not want to write this post.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: