I did not want to write another blog post.

Quick backstory and why we’re back here

If you’re new to this story I’d recommend checking out Gelman’s write-up summarizing the history behind the retraction. As per the journal, the paper was retracted due to:

lack of transparency and misstatement of the hypotheses and predictions the reported meta-study was designed to test; lack of preregistration for measures and analyses supporting the titular claim (against statements asserting preregistration in the published article); selection of outcome measures and analyses with knowledge of the data; and incomplete reporting of data and analyses.

In lay terms: outcome switching, covering it up, data-dredging/cherry-picking, and selective reporting.

As I noted in a previous blog-post, I’d hoped that the retraction would do enough to set the record straight. Since then, several of the authors have done the rounds in various news outlets framing this as a mistake attributable to accidentally incorporating a single line in the main text. In doing so, they’ve not engaged with the more substantive concerns that warranted retraction, nor the causal issues we raised in the matters arising. They’ve done this in Nature, the Wall Street Journal and most recently on Spencer Greenberg’s podcast

The need to set things straight

It would be great to drop this and not write about it ever again. But here’s the rub: We were asked by the editors to summarize the reason for retraction in our matters arising, and in misrepresenting why the paper was retracted the authors are publicly claiming my published work is incorrect. Here it is on display in Nature

Here, Nosek attributes the findings of the investigation to us. The investigation involved four domain experts, several editors, and a whole bunch of higher-ups in Springer Nature (as is policy). The result is that a very well known scientist is publicly asserting my work isn’t robust. Critically, they have offered precisely zero evidence to support their claims. Here, we’ll go through the relevant evidence that is publicly available. Instead, as best as I can tell, they are just lying. Given this has now led to misleading articles in multiple higher-profile venues, it’s probably time to set the record straight.

Fact-checking the Greenberg podcast

There is a secondary and quite interesting story about why, precisely, the journalists who have interviewed the authors have simply taken their word for it and rarely pushed back. It’s not exactly the norm for high-profile retractions, but it has given the authors a bit of a bully pulpit to work from. Spencer to his credit, pushes back a little, but didn’t seem to know the facts well enough to really get to the root of thigns. As his podcast was the longest and least-cropped interview, It’s helpful for sorting fact from fiction.

One pesky inaccurate sentence?

On the reason for retraction, the authors keep emphasizing that a single sentence was inaccurate and they agree the paper needed to be retracted as a result. This is just untrue. Per COPE guidelines retractions occur for issues substantial enough that the findings are no longer reliable. Here’s Nosek echoing this when speaking to greenberg.

The paper was challenged as published in 2023. Some attentive readers were surprised to read a statement in it that said every analysis reported here in the individual experiments… Every one of those experiments was pre-registered, and the meta project, these analyses aggregating all of the results across these 80 experiments, was pre-registered. That was a definitive statement that is false. It was in our paper claiming that we pre-registered all these things, so these reforms that we’ve been talking about and promoting. They raised that in a commentary, saying, “In addition to substantive critiques of, we don’t think you can conclude that you observed high replicability for X, Y, and Z reasons. We think the design wasn’t appropriate for testing that question for these reasons.” There’s lots of substantive critique in the ordinary variety, but it opened with this observation of a fundamental critique of failure of this pre-registration statement.

Or a host of them.

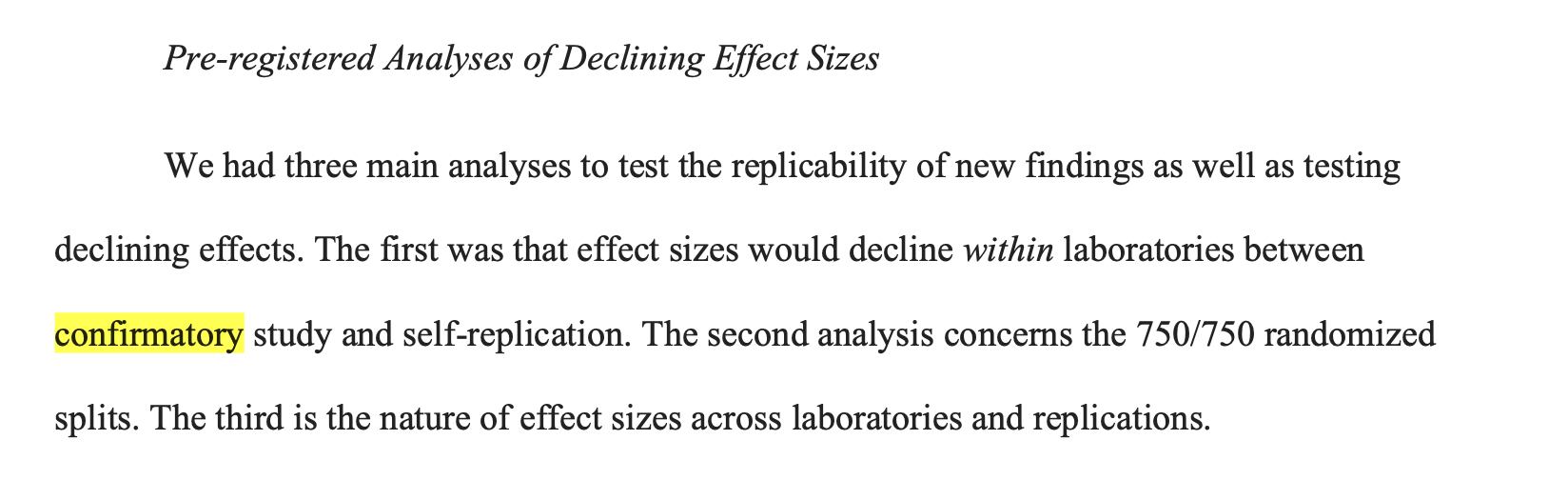

What Brian is obscuring by emphasizing this sentence is that the paper affirmatively described what was pre-registered in three separate parts of the paper. It’s easy to see how a sentence accidentally found its way in, much harder to see how these authors would make that mistake thrice. Descriptions of what analyses were confirmatory appear in the main text and supplement, in sections called “confirmatory analysis”. Per Brian’s previous work “confirmatory analysis” implies the presence of a preregistration (e.g. prediction vs. postdiction).

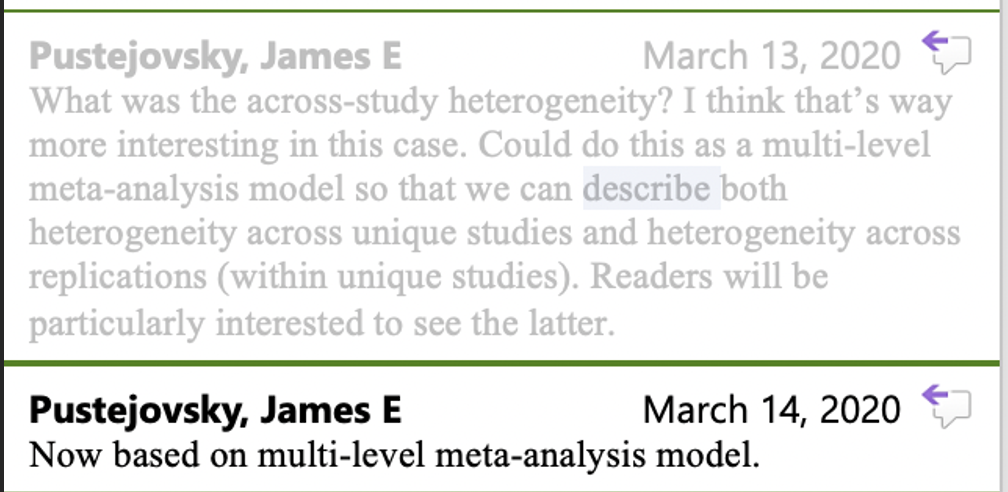

The main text listing of confirmatory analyses contains three subheadings. The first of the analyses described is a meta-analysis added to the paper in spring of 2020 by James Pustejovsky while revising the paper with Protzko. As the data were analyzed and originally presented in fall of 2019 (we’ll get back to this), this cannot have been preregistered:.

The supplement’s confirmatory analysis section (P.38-39) similarly affirms that replicability rate was pre-registered, and notes other post-hoc or deviated analyses as confirmatory studies and even includes a previously-explicitly-exploratory analysis as confirmatory (Lab-specific Variation, page 7). It even includes a section called “pre-registered analyses that quite sparsely describes what they actually preregistered in 2018 and again in 2019.

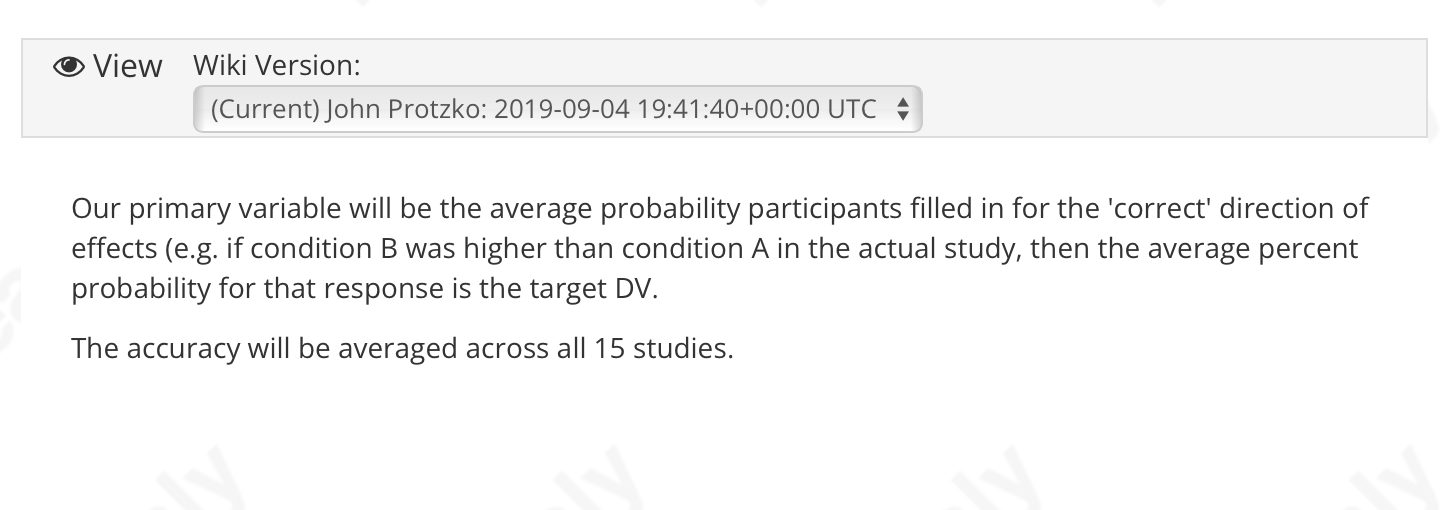

As icing on the cake, they even claimed their expert prediction study was pre-registered. I think that is a grand claim, given this was the preregistration:

In the text (supplement), the results of this study are reported as follows:

The Spearman correlation between prediction accuracy and observed effect size was .104, p = .712, two-tailed.

So here, their statements of preregistration refer to a frozen wiki-page describing a wholly different DV (averaged accuracy) tested with a non-parameteric test against an unmentioned IV (effect size). Does this seem preregistered? Did they forget here too, to check what they had planned?

Returning to Brian’s version of events, the reasons “statements” was plural in the retraction note is that the paper is replete with multiple affirmations of preregistered analyses that were not, in fact, preregistered or not preregistered as described.

The deviations raise a broader question… how could they not notice that any of the analyses involved deviations and disclose them? In 2023 when writing up the paper. Even if that line snuck in, you’d think someone would say

“Hey hoss, didn’t we change this analysis to remove the decline effect bit in revision, should we disclose that?”

In focusing on a single sentence, it is much easier to sell the story that this was a big accident.

But the preregistration is beside the point.

Yet the preregistration claims alone aren’t the reason the paper was retracted. As the retraction notice states, the pregistration claims matter in relation to a broader pattern of failing to be transparent about the meta-project’s original purpose. The authors have repeatedly denied that this finding of the investigation is correct. In the podcast, Spencer asks Brian whether the authors engaged in outcome switching and failed to disclose the original intent of the study. Here’s Spencer’s question and Brian’s response.

Brian here is arguing that decreasing the prominence of the decline-effect related analysis and motivation is not an indication that the study switched its motivations. He says its reasonable for us to think that, but goes on to say it isn’t the case.

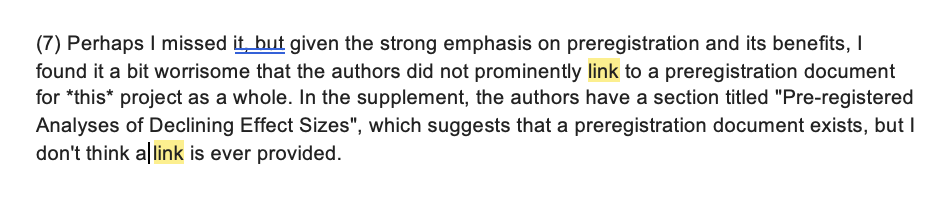

Fortunately, I didn’t rely on vibes when raising these concerns. Instead, I just looked at the documents they shared. Tal Yarkoni, in his review at Nature sensed the outcome switch, noting:

Third, I found the recurring “decline” theme throughout the article fairly puzzling. It seems poorly motivated and at odds with the overall framing of the manuscript as a test of whether or not replicability is possible in psychology…Again, if the intent here is to test for some kind of supernatural observer effect, then that should be clearly disclosed, and the reader can decide for themselves how to interpret that.

This makes it clear that in the version reviewed and rejected at Nature the authors had transparency issues surrounding clear design choices intended to test supernatural effects. Yarkoni sensed it, likely knowing Schooler’s past work, and asked the authors to be honest about it.

And it’s not just Tal Yarkoni. Reviewer Daniel Lakens also sensed that the project was about the decline effect but not being clear about that fact.

Here’s the author’s response to Yarkoni:

Brian’s statement makes it as though the outcome switching was gleened from reading the tea-leaves of relative emphasis of replicability vs. the spooky decline effect. Yet, here, the authors explicitly state that they lessened the prominence of these hypotheses because the findings were null. Switching from a null outcome to one that supports a wholly different claim is… well… outcome switching.

Schooler’s hypothesis, which is the reason the project was funded, is only described as “According to one theory, declines in ESs over time are caused by a study being repeatedly run.” This doesn’t make it clear it is one of the author’s theories, and that it motivated the funding, design, preregistration(s) and analysis code. Similarly, the SOM only refers to these original hypotheses as “unusual explanations.” You have to dig deeper in the supplemental materials before you start scratching your head wondering what “observer effects” are.

To top it off, the authors elected not to release the code corresponding to these preregistered analyses with the original paper (another oversight?). They also removed effects from the published code which corresponded to the decline effect as preregistered. Between the response to reviewers and the current description of the pre-registered hypotheses and their motivation, severe outcome switching and failure to disclose original intent is unambiguous.

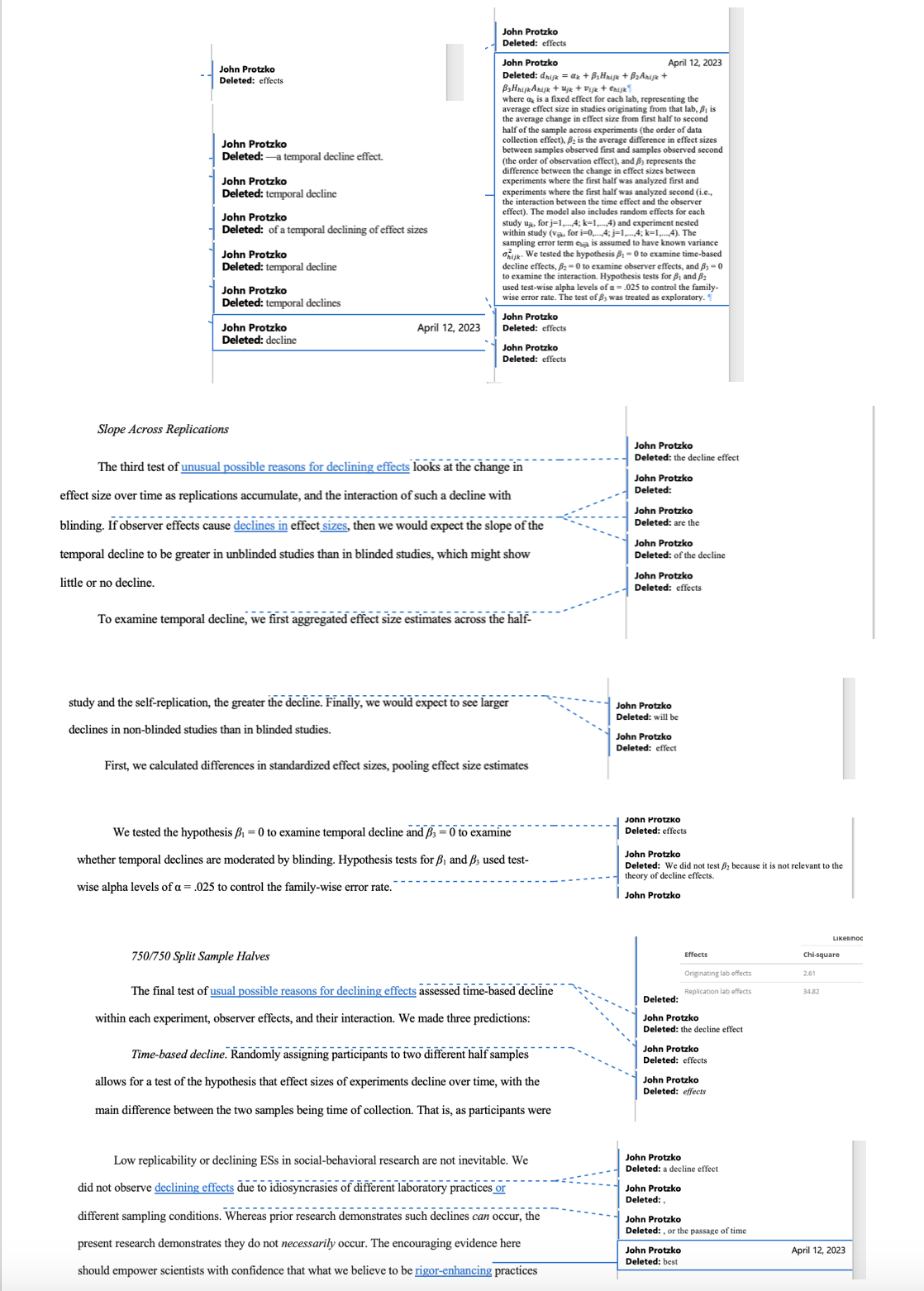

To really drive this home, here’s a hastily made collage of the revision edits showcasing a purging of “the decline effect” from the text. They even purge “the passage of time” from the main text, consistent with their undisclosed removal of terms from statistical models which indicate interest in the passage of time. This seems like a pretty active attempt, in response to Yarkoni’s concerns, to distance the project from the very things they preregistered.

Now, here’s the kicker. As the authors note, they didn’t want to “dwell” on the decline effect. Yet the supplement contains text lifted from the preregistrations, so somehow they had to forget what was in the preregistrations while… reading and revising text containing aspects of the preregistrations (which are, incidentally, not clearly identified as such).

“Of course we planned to study replicability”

The reality is that there is very little doubt what they set out to measure and, by extension, what was not planned a priori. The reason we know this is that the authors actually did a fantastic, thoughtful and thorough job preregistering the supernatural tests. From the earliest documentation on the project through two-pre-registrations the hypotheses remained the same. They hired a statistics consultant to turn these hypotheses into tests. They even wrote code, blind to data, specifying precisely what analyses they planned. Code they modified substantially post hoc for the main analysis, and then just did not share.

If you download that code, the 09-03-2019 version has an option use_real_data set to TRUE. This makes it clear that they indeed analyzed the data, using this code, on September 3rd of 2019. As of their initial analysis of the data, on code they spent months preparing, following a preregistration that closely matched the original grant proposal from years earlier… they did not measure replicability. They don’t even calculate whether the results are significant for any of the experiments or replications! There is no indication of anything other than the supernatural and observer-based hypothesis tests until the very moment they analyzed the preliminary data.

In the podcast, Brian takes a fairly tortured line of reasoning that they didn’t think it was necessary to preregister the meta-project. The original replication efforts from ~2015 weren’t, so why would they think to preregister these? Well, that too is a bit of an obfuscation because other replication efforts projects since then have been preregistered. Most memorably, Many Labs 4 which… resulted in concerns the authors deviated from their preregistration in ways that made the finding spicier.. Elsewhere, the early (2013) start date of the project is implied as a reason for not preregistering but the pre-registrations for this project were completed in 2018 and 2019.

Are we to believe that this was the plan all along and the lead authors and stats consultant simply forgot over two years of developing the analysis plan and code, only to remember after analyzing the data? That they didn’t believe meta-studies needed to be pre-registered even though just months later Nosek was involved in a project that thoroughly preregistered which metrics would be used to evaluate replicability? It strains credulity.

This argument that they did not think it was necessary raises more questions than it answers, and I’m surprised journalists haven’t pushed back. If that was the case, wouldn’t they have known when revising in 2023 and then simply said that in response to reviewers? If, as Brian suggests, they wrestled with ideas of how difficult it was to determine how to measure replicability—where is that in the manuscript? Why not be transparent and instead present everything as planned all along? Elsewhere, the authors get into similar problems asserting that they didn’t realize how many choices they would have during analysis. Why not describe this? Their version of events requires us to believe they did not think it was necessary to preregister, realized how many analytic choices they had, and inadvertently wrote it up as though they’d preregistered… while simultaneously believing they had planned this all along but simply forgot to preregister.

If you have any doubt the replication analyses were posthoc, check out the first part of this series that I hope will end with this post. Also, you can read the retraction note which affirms this is all true following a lengthy long investigation in which the authors had ample time to provide any documentation to the contrary. While I was not privy to any of this, I imagine even an email from early 2018 saying “here’s how were we measuring replicability and demonstrating it is high” would have gone a long way. Indeed in the interview and elsewhere the authors seem to indicate they didn’t realize how complicated it would be to select metrics until they analyzed the data—they were indeed selected with knowledge of the results! If you feel the journal erred in their decision, please write up why!

How did this happen?

The last thing that needs clarity is the “no idea how it happened” refrain we keep hearing. Here it is in Greenberg’s podcast:

I’ll assume Brian hasn’t looked at the documentation they added, because we know exactly how this happened and why.

The version submitted to Nature did not have a link to the decline effects preregistration, and did not indicate everything was preregistered. Yarkoni noted this seemed strange, given the overall focus of the paper.

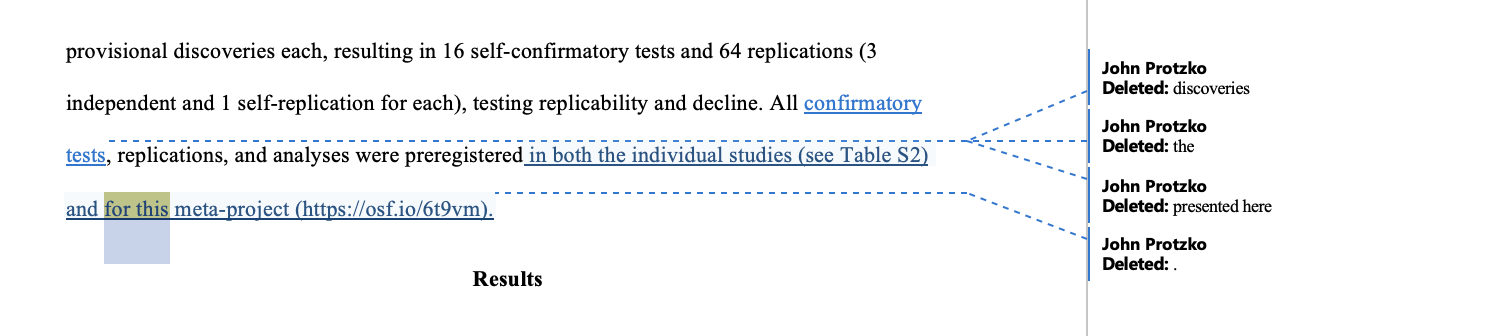

So how did that pesky line get added? Well, in the revision for resubmission it was added by John Protzko.

First, we keep hearing this “many cooks in the kitchen” excuse but the document history reveals that the vast majority of revisions relevant to the retraction were done by John Protzko. Or from his logged-in Microsoft word account.

Notably, the historical documents indicate that John Protzko drafted the original preregistration, used a hired consultant for feedback, went through rounds of revision, preregistered it in 2018, then summarized it again in a second preregistration in 2019. The edit history shows he was actively involved in the addition of post-hoc results and changing metrics. At some point in time, the pre-registered code got cribbed over to the main analysis code, modified and several additional analyses were added.

Against this backdrop, when asked explicitly by reviewers if these analyses were preregistered, this line was added. When they were asked by two reviewers to clarify if they had intended to study a supernatural phenomena—they removed virtually all references to the original hypothesis and its motivations.

Hanlon’s Razor

Hanlon’s razor has been along for quite the ride with this paper. It states:

Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.

Nosek’s story of the retraction invites us to conclude honest error (Hanlon’s stupidity). It tells a nice and tidy story of a plan to conduct analyses of these sort since 2013, that somehow went missing from the pre-registration because no one realized you should preregister such things back then. When write-up happened, this little line snuck its way in–what with all the co-authors and stuff. It invites us to marvel at the folly of so many authors in not noticing.

Yet Hanlon’s razor begins to strain when you realize the line Nosek emphasizes was written by the very same author who penned and submitted the two pre-registrations across multiple drafts. That the pre-registrations were done in 2018, not 2019. That the very same author had worked with a hired statistics consultant to produce analysis code, blind to data, which made no mention of replicability. It’s hard to see this line as an accident when variants of misrepresented preregistration occur not just in this line but in two additional sections and for an entirely different experiment–also “preregistered” by the very same lead author. It gets somewhat harder still to assume honest error when the line was added in response to reviewers who found themselves surprised no explicit claims of preregistration for the meta-project were made (only “confirmatory analyses”).

Perhaps we view all of this and still see incompetence rather than malice. Now we have to grapple with how incompetence could result in the authors systematically and very meticulously removing from the main text any indication they set out to study supernatural effects. This clearly, as per the authors response to reviews, occurred in response to two reviewers sensing it and asking them to come clean. That they forgot, when revising to refer to fringe theories, those theories originated with last author on the paper–even as they cited the work he wrote on the topic. That none of this occurred to them when Lakens and Yarkoni’s reviews seemed to sniff out the outcome switching in 2020. “Nope, no outcome switching here… we preregistered everything… right guys?”

Returning to the interviews

In the Wall Street Journal article, Leif stated “It wasn’t because we were trying to fool someone, but it is because we were incompetent”. The piece in Nature quotes Brian saying, “I don’t know how many times I read that paper with these erroneous claims about everything being preregistered and missed it. It was just a screw up.” The piece, in its title, indicates the authors are doing some soul-searching.

If we still believe incompetence, not malice, to be the case, than the incompetence appears to continue to this day. Brian seems to have somehow missed during the investigation and multiple read-throughs that more than one statement was inaccurate. He seems to not be aware that the documents his team released make it unambiguous who added that line. he doesn’t know that the preregistrations occurred in 2018 and 2019, replete with blind analysis code that made no indication of an intent to study replication. He missed or forgot that the authors, during revision, explicitly told the reviewers they were distancing themselves from the original hypothesis.

At this point, I’m personally inclined to believe the authors are choosing to continue the very fabrications that motivated the retraction in the first place. It seems they are still lying, and misleading journalists much as they did readers about what they planned to study, what they preregistered, and the history of the project as a whole. That—much like in their response to reviewers—they’re still choosing to ignore the substantive critique and spin things in a positive light. I can see why the incentives would push things this way—its very hard to admit you engaged in the very same thing you’ve built careers rallying against.

The authors are welcome to prove me wrong. They can start with the unambiguous stuff. They can reach out to journalists and correct their statement that a single line motivated the retraction, acknowledging the other two sections as well. They can clarify that it was the journal’s finding, not ours and ensure that the pieces acknowledge daylight between the motivation for retraction and our critique on the causal claims which do not depend at all on the issues with preregistration. They can clarify for Spencer that they, at least now, know exactly how that pesky line wound up in the paper and sort out what led Protzko to forget the two preregistrations when writing it.

Then they can work towards the ahrder bits… acknowleding that it isn’t the relative prominence of in the article that leads to a conclusion of outcome switching, but two preegistrations and analysis code applied to data which make no mention of their ostensibly long-running plan to analyze replicability. They can point the journalists towards evidence which clearly indicates many of these analyses were post hoc, with knowledge of the data, evolved over time. They can clarify that they actively, in response to reviewers, removed language indicating Schooler’s hypothesis that catalyzed the whole project. In short? They can take ownership of the outcome switching, post-hoc analyses presented as being a priori, and hacking and cherry-picking of metrics. If they want to defend their findings, they should start from acknowledging earnestly how they arrived at them.

I won’t hold my breath. Early on, I emailed the authors and offered to walk them through this. In the wake of WSJ, I emailed Leif and sent along the detailed concerns that I had originally shared with the journal. I wrote a past blog post that at least one of the authors certainly read, pointing them to unambiguous evidence. My offer to hop on a Zoom and walk them through the issues was first made a year ago, and it still stands. If they don’t trust me… Stephanie Lee covered a lot of this as well. Perhaps they could chat with her, as they have before on other cases of science gone awry.

So far, there has been no engagement with any of the evidence and only continued statements that conflict with it. Perhaps they just have a tiny bit more soul-searching to do.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: